Someone made a joke.

“Why not collect the ice off our ponds and sell it in the tropics!’

Everyone at the party laughed. They were all keen enough to make money, and there seemed plenty of ways to do it in the United States of America at the beginning of the 19th century. But to take the ice from the ponds around their city of Boston during the freezing winter months, and try to ship it to the hot, steamy islands of the Caribbean! It would all melt away, taking their money with it!

Frederick Tudor – A Man with a Mission to bring ice to the World

Before the year was up he had shipped 130 tons of ice from Boston to the tropical island of Martinique

However, to twenty-one-year-old Frederick Tudor, it was an idea to work on. Before a year was up, in 1806, he shipped 130 tons of ice south from Boston, Massachusetts, to the tropical island of Martinique in the West Indies.

Tudor became the ‘Ice King’ so that by the 1840s clear, natural ice from the ponds of Massachusetts cooled drinks half a world away: in India, China, Australia, the Philippines.

Tudor spent years battling with the technical problems of how to stop ice melting. He built special ‘ice-houses’ at the ports where his ships berthed, then experimented with ways of insulating them, using straw, wood shavings, even blankets. Watch in hand, he would stand outside each newly insulated house in the hot sun, measuring the rate at which the ice melted. He succeeded in designing a tropical ice depot where only 8 per cent of the stored ice melted in a season. Tudor persuaded the local populations to enjoy iced drinks, ice-cream, chilled fruit, and all the other luxuries ice could bring. In winters when not enough ice formed on the ponds, Boston sea captains braved the Labrador icebergs and chipped off big pieces to take south. But these odd-shaped lumps of ice were difficult to stack and melted easily.

Tudor spent years battling with the technical problems of how to stop ice melting. He built special ‘ice-houses’ at the ports where his ships berthed, then experimented with ways of insulating them, using straw, wood shavings, even blankets. Watch in hand, he would stand outside each newly insulated house in the hot sun, measuring the rate at which the ice melted. He succeeded in designing a tropical ice depot where only 8 per cent of the stored ice melted in a season. Tudor persuaded the local populations to enjoy iced drinks, ice-cream, chilled fruit, and all the other luxuries ice could bring. In winters when not enough ice formed on the ponds, Boston sea captains braved the Labrador icebergs and chipped off big pieces to take south. But these odd-shaped lumps of ice were difficult to stack and melted easily.

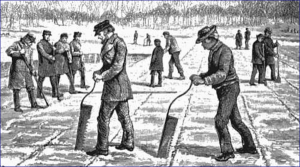

Every winter, hundreds of labourers descended on the ponds to harvest the ice

Tudor asked a friend to invent a machine which chopped the surface of a pond into neat ice cakes all the same size. Packed together with sawdust or straw, a heap of these blocks could last beside a pond for several years, like an untidy ice castle. Every winter, hundreds of labourers descended on the ponds to harvest the ice. Lucky Australian gold-diggers toasted their new wealth in Melbourne pubs with drinks cooled by Boston ice. A Persian prince sent Tudor a message of gratitude for ice which was saving the lives of patients in Persian hospitals: placed on the forehead it helped to lower fevers.

A Persian prince sent Tudor a message of gratitude for ice which was saving the lives of patients in Persian hospitals

Tudors efforts to conserve and move ice though weren’t unique though. Farmers around the city of London in the 1830s used to flood their fields at the beginning of winter. Everyone helped to pile the first thin sheets of ice into carts, for delivery in the city. In the middle of November ice could fetch 15s a cartload. Thousands of tons of ice were stored in a big underground ice-house where, with luck, some of it lasted all through the summer. It was used to keep the fish fresh on London fish stalls.

Ice as a Preserver of Food

Ice is one of the oldest and best preservers of food. At low temperatures the bacteria which cause food to deteriorate are either destroyed or become almost inactive. But natural ice by itself is a very vulnerable refrigerator. Even in cold climates the weather can play tricks, unexpectedly melt the ice and spoil carefully-stored food.

In the late 19th century America suffered the “great ice famine’. The warmest winter on record was followed by a hot summer. All the stored ice had melted by July, and the newspapers were filled with lurid stories of putrid meat, soured milk, and epidemics of typhus.

What was needed was a way to make ice artificially and cheaply, wherever and whenever anyone wanted it.

Ice-Making Machines

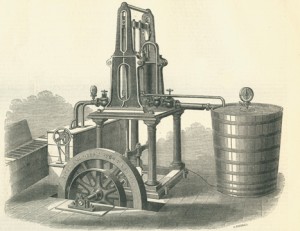

Ice-making machines began to be designed and patented in the 1830s. One of the best was developed in Australia by the editor of the Geelong newspaper, James Harrison.

The big problem in Australia in the middle of last century was surplus meat. It wasn’t practical to send sheep or cattle alive by ship to European markets and vanned meat wasn’t very popular.

The big problem in Australia in the middle of last century was surplus meat. It wasn’t practical to send sheep or cattle alive by ship to European markets and vanned meat wasn’t very popular.

Millions of Australian sheep were boiled down for tallow, which was shipped to England to make soap – At least the hungry English workman could wash his hands cheaply before he ate his expensive, locally produced mutton.

Harrison believed that ice was the answer. He remembered that, as a child in Scotland, he had seen his father and other fishermen using American pond ice to preserve their salmon catch. Harrison believed that if meat carcasses could be frozen they would last the long sea journey across the Equator to England, and arrive in good condition.

In 1857, after several years’ experimenting, he patented a process which produced the first synthetic ice in Australia. Experts agreed it was ‘much more complete and practical than any other process’ so far invented.

In 1857, after several years’ experimenting, he patented a process which produced the first synthetic ice in Australia. Experts agreed it was ‘much more complete and practical than any other process’ so far invented.

The next problem was how to keep the meat frozen. This meant designing a machine to produce cold: a refrigerating machine. Harrison worked on this in between editing his newspaper and being elected to Parliament. In 1873 he was ready.

The Americans had already developed a way of sending chilled meat by ship to England. Their method, keeping meat in a chamber surrounded by ice, worked for a short sea voyage. But the inside of the meat never became really cold and Harrison knew that deterioration would set in during the weeks it took to cross the oceans from Australia. His method froze the carcasses right through. In 1873 guests at a special banquet in Melbourne ate meat, poultry and fish that had been frozen and kept for six months.

‘Equal to newly killed meat of good quality and full of flavour’

Later in the year, a ship fitted with Harrison’s special refrigerated chamber sailed from Melbourne for London with twenty-five tons of frozen prime beef on board. But no one really knew how to handle the machinery, and the beef arrived partly thawed, and bad. Poor Harrison was ruined.

Their first cargo of frozen meat and butter reached London on the steamer Strathleven early in 1880

Several years later, in 1879, the first shipment of frozen food to reach its destination in an eatable condition arrived in France from the Argentine. Another Australian attempt, backed by businessmen and sheep owners, and using the method of a French inventor living in Sydney, had just failed. Two young Scottish shipowners finally solved the Australian problems with newly designed refrigerating equipment. Their first cargo of frozen meat and butter reached London on the steamer Strathleven early in 1880.

Amidst great publicity and rejoicing, officials had a banquet on board and found the Australian food most enjoyable. A profitable trade began, carrying migrants to Australia and meat back.

Freezing Food Takes Off

Freezing can preserve food whole and raw. Now animal carcasses could be sent around the world. Refrigerated railway trucks shifted produce from where it was grown to where it was needed. Here, in addition to canning, which had been developed at the beginning of the century, was a new way of preserving surplus foods. Families began to install a new piece of kitchen equipment, the ice-box. And factories churned out tons of artificial ice.

Drawbacks

as it thawed, the cell walls collapsed, the fluid ran out and the food became soggy and tasteless

The trouble with frozen food was that it did not taste the same as fresh food. Some foods lost their flavour when they thawed, some became mushy and inedible. The reason was discovered by a German researcher, Max Planck, who was not directly interested in the food industry, but in the structure of crystals.

Planck found that when fluids freeze, there is one temperature at which especially large crystals are formed; he called it the zone of maximum crystallization. The cells of foodstuffs are largely made up of fluid and their zone of maximum crystallization is just below freezing point, between -3.9C and -0.5C. The sharp edges of the large crystals tended to pierce the cell walls. Nothing showed as long as the food remained frozen. But as it thawed, the cell walls collapsed, the fluid ran out and the food became soggy and tasteless.

Over several years he worked out methods of freezing food so fast that it went through the zone of maximum crystallization in a few minutes

In the early 1920s Clarence Birdseye was in Labrador on a hunting trip. He noticed how fish, kept outside in the sub-zero temperature, froze immediately and tasted really good even months later. Of course, this is the way Eskimoes have always stored their food. Back in America, Birdseye experimented with ways of freezing fish as quickly as possible to preserve their flavour. Over several years he worked out methods of freezing food so fast that it went through the zone of maximum crystallization in a few minutes, instead of taking several hours as before. This way, the large dangerous crystals had no time to form. No equipment existed for the quick freezing of food, so Birdseye had to develop his own machinery. By the end of the 1920s the first packages of frozen food were on the market.

Today, almost all foods can be bought frozen. A new era of ready-cooked foods has begun, changing our eating habits.