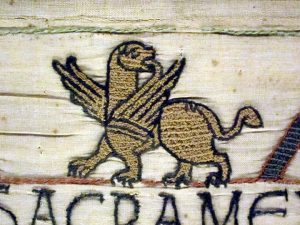

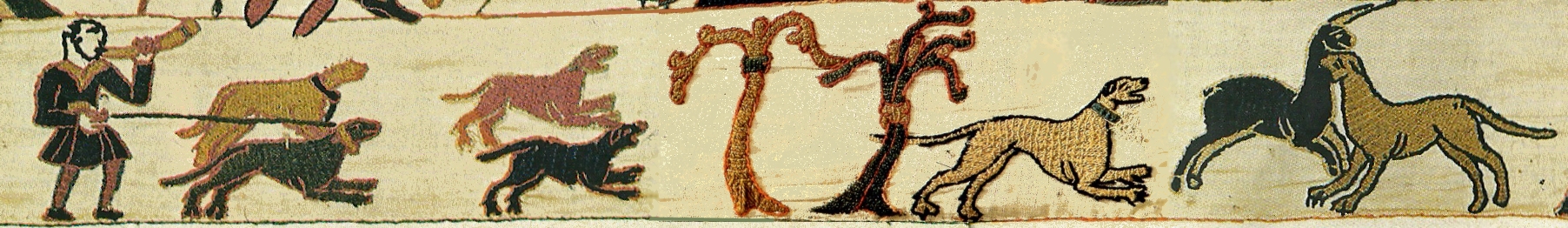

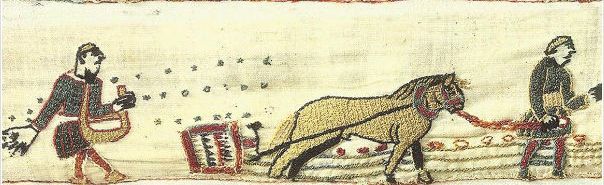

The Bayeux Tapestry tells one of the most famous stories in British history – that of the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, particularly the battle of Hastings, which took place on 14 October 1066. But who made the tapestry and how long did it take?

Who Made the Bayeux Tapestry ?

Who Made the Bayeux Tapestry ?

We have no sources to tell us who made the Bayeux Tapestry; however, most scholars agree that it was made in Norman England, probably by Anglo-Saxon embroiderers. At present we do not know how many people were involved in creating the Tapestry. We can say it would have been embroidered by women because all the surviving evidence demonstrates that only women in early medieval England embroidered.

Men could have created the design, however – there is a famous example where Ӕthelwynn, a 10th-century noblewoman known for her embroidery work, wrote to Saint Dunstan (c924–88) asking him to design an embroidery pattern for a priest’s stole that she and her girls could embroider in gold. Also, monks were well versed in drawing and transferring images onto manuscripts for illumination, so it is not unlikely that men were involved in this part of the process.

Men could have created the design, however – there is a famous example where Ӕthelwynn, a 10th-century noblewoman known for her embroidery work, wrote to Saint Dunstan (c924–88) asking him to design an embroidery pattern for a priest’s stole that she and her girls could embroider in gold. Also, monks were well versed in drawing and transferring images onto manuscripts for illumination, so it is not unlikely that men were involved in this part of the process.

Women in Anglo-Saxon England were famed for their embroidery skills. Documentary sources tell us that embroidery was considered a commendable occupation for women in elite circles, while the Domesday Book and the 12th-century chronicle Liber Eliensis both highlight women who embroidered as a profession. Written sources for embroidery production in Normandy point to it being a “worthy occupation” for high-ranking Norman women.

Previously nuns or elite women were thought to have made the Bayeux Tapestry. However, recent research studying the embroidery’s technical attributes as seen on the reverse of the hanging shows the embroidery was stitched to a set standard, indicating a certain level of training. Meanwhile, certain motifs were worked to set formulas – for example, the castles can be divided into three groups: outlines stitched first, then fillings; blocks of colour stitched from left to right and top to bottom; or simply different colours stitched from left to right. This all points to the possibility of three workers (or groups of workers) completing all the castles featured in the tapestry. This, combined with the fact that each of the eight panels of ground fabric was embroidered before they were joined together, means that they could have been worked simultaneously and leads to the conclusion that a sophisticated level of overall organisation was required.

Previously nuns or elite women were thought to have made the Bayeux Tapestry. However, recent research studying the embroidery’s technical attributes as seen on the reverse of the hanging shows the embroidery was stitched to a set standard, indicating a certain level of training. Meanwhile, certain motifs were worked to set formulas – for example, the castles can be divided into three groups: outlines stitched first, then fillings; blocks of colour stitched from left to right and top to bottom; or simply different colours stitched from left to right. This all points to the possibility of three workers (or groups of workers) completing all the castles featured in the tapestry. This, combined with the fact that each of the eight panels of ground fabric was embroidered before they were joined together, means that they could have been worked simultaneously and leads to the conclusion that a sophisticated level of overall organisation was required.

It can therefore be hypothesised that a ‘manager’ was in charge of the production process. This person would have needed knowledge of embroidery working practices, so it is likely that it would have been a professional embroiderer who was familiar with training and organising others and had experience working on large commissions. This level of organisation would need to have taken place in a professional workshop-like setting. Anglo-Saxon charters give examples of possible workshops – for instance, one dating to the ninth century records Bishop Denewulf of Worcester giving an embroiderer named Eanswitha an estate as payment for looking after and making textiles for the church. This estate most likely housed some form of workshop, much as other central estates are known to have done for textile production.

How long would it have taken to make it?

How long would it have taken to make it?

It is difficult to say how long it took to make and there has been no specific research on this. The answer would depend on how many women were working on the embroidery simultaneously; the size of the building(s) in which it was being made; access to light and access to materials. Any estimation of the time taken to make the tapestry would need to take into account the time taken to manufacture the required materials; plus the time involved in the production of the design itself; plus other logistics. From an embroiderer’s perspective, the stitches employed are not particularly time-consuming to work.

It is difficult to say how long it took to make and there has been no specific research on this. The answer would depend on how many women were working on the embroidery simultaneously; the size of the building(s) in which it was being made; access to light and access to materials. Any estimation of the time taken to make the tapestry would need to take into account the time taken to manufacture the required materials; plus the time involved in the production of the design itself; plus other logistics. From an embroiderer’s perspective, the stitches employed are not particularly time-consuming to work.

RELATED ARTICLES

|

1066 and all that … the day the Channel Islands became part of England |

|

The Normans – A Timeline |