As the 19th century gave way to the new 20th century few could appreciate how much of the old cosy world order was being swept away by industialisation, science and the increasing political enfrachisment of the masses. In Guernsey at this time there was to be one last gasp of the old superstition and occult, ‘The Last Witchcraft Trial in Guernsey’.

An Alarm is Raised

Early in the morning of 16 January 1914, PC Adams was called out to the harbour master’s office in St Sampson’s. A local woman, Mrs Houtin, had banged on the doors of the office ‘in an agitated state’, demanding police protection and sobbing with terror because ‘a spell of witchcraft had been put on her’ for non-payment of a £3 debt and unless she paid immediately, she had less than a week to live.

She did not have the money to pay and she was hysterical – so much so that PC Adams feared for her sanity and worried that she might even try to kill herself. The constable knew that Mrs Houtin was a Roman Catholic and he managed to persuade her that she should go to see the local priest, Canon Foran.

The canon could offer little in the way of help, except to suggest that she go home and pray. But he did manage to calm her down enough for PC Adams and a colleague, PC Lihou, to take a statement from her the following day.

The woman, however, was still clearly terrified. When the policemen arrived at her house, PC Lihou said that she had refused to open the door to them at first. When she did finally let them into the house, she said she was ‘being driven mad by the evil eye’.

She had gone to St Peter Port police station in the early hours of the previous morning pleading for help but had simply been sent back to St Sampson’s. That was why she had been banging desperately on the door of the harbour master’s office at half past six in the morning.

To calm her, PC Lihou conducted a preliminary search of the premises, but all he found was a box of powder in the outhouse and some charms for members of her family.

The woman recoiled in fright at the sight of his discoveries and said that she was afraid to touch the box and thought it was ‘full of little devils’.

The ‘Witch’

Mrs Houtin kept a farm at Croute Fallaize in St Martin’s. The previous summer her husband had died unexpectedly. Then, in October, someone, she said, had ‘bewitched’ her cattle and they all died. She was also suffering from bad headaches and in desperation had gone for help to a woman named Aimee Lake (nee Queripel), who lived at Robergerie, St Sampson’s.

Mrs Lake made a living for herself and her children by ‘reading the cards’, telling fortunes, explaining the significance of dreams and dispensing charms made of harmless, everyday ingredients such as flour, starch and baking powder.

She made some tea for herself and Mrs Houtin and they chatted companionably. Afterwards she read the tea leaves in the latter’s cup, which told her that Mrs Houtin was under a spell – just as her late husband had been at the time of his death.

Mrs Lake gave Mrs Houtin some salt to throw at her enemies and some ‘magic’ powders. She was to burn some and bury the remainder in the garden.

This she did, but although the powders had taken away her headaches, she was so ill after carrying out Mrs Lake’s instructions that, tended by her daughter, Rosine Goubert, she spent three days in bed recovering.

She had paid Mrs Lake 15 francs in October 1913 for these powders, followed by £2 15 s (£2.75) shortly afterwards. Now Mrs Lake was telling her that she had put a spell on her and unless she paid another £3 by Friday 23 January 1914, she would die.

The Arrest

On 20 January 1914, The Star reported that Mrs Lake had been charged by Constable E. H. Ogier of St Sampson’s with ‘fortune telling, the explanation of dreams and with practising the art of witchcraft from August 1913 till the present day’.

When charged, Mrs Lake fainted. When she recovered, she panicked. At first she denied the allegations but when she was shown ‘certain charms’, she collapsed and begged forgiveness. She would give refunds to everyone. She never charged for fortune telling, though she would accept donations. She was only trying to help. She had never intended to hurt anyone. She would apologise to everyone. It was not enough – this was not the first complaint to be made against her and the police intended to take action.

Meanwhile, PCs Adams and Lihou dug up a number of packets of powder buried about two feet deep in Mrs Houtin’s back garden at cardinal points of the compass. The holes for the powder had been dug by her son, Ernest Louvel, and he had watched his mother bury them. He believed that they were supposed to drive away witches and the ‘evil spirits’.

Other witnesses came forward. One of Mrs Lake’s employees claimed that she had seen her mistress telling fortunes with cards. Marie Roger said she had paid Mrs Lake £3 10s for some advice and was given a ring to keep spells off her while she was in Alderney. Felicite Garnier, a child of 10 who lived with Mrs Roger, said she had seen Mrs Lake burning powders.

The Trial

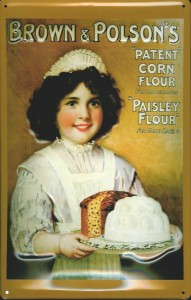

When she came to trial, Mrs Lake defended herself by saying that people came to her of their own free will and asked for help. She denied that she was a witch and said that she simply tried to help those with problems through the use of her special powders. However, by this time, the powders had been analysed. They contained baking powder and brown starch plus copious quantities of Brown and Polson’s cornflour, from which blancmange was made. Another of her employees, Emily Radstone, said that she regularly bought quantities of ground rice and Brown and Polson’s cornflour for Mrs Lake.

The question then faced by the court really boiled down to the question, “could there really be magic in simple blancmange powder?”.

It appears that the Guernsey Royal Court seriously thought there could.

It appears that the Guernsey Royal Court seriously thought there could.

Possibly not helped by the fact that a distant ancestor of hers, Alechette Queripel, had been burned at the stake as a witch in 1598, Mrs Lake was found guilty of witchcraft and sentenced to eight days’ imprisonment.

Mrs Lake protested her innocence vehemently and asked what would become of her ‘fatherless little children’ if she were sent to jail. The Sheriff told her not to worry and said that he would take care of them until her release. He seemed determined that she should go to prison for practising her witchcraft.

HM Comptroller sensibly said that Mrs Houtin had suffered natural misfortunes and that Mrs Lake had gone too far in demanding money with menaces from stupid and gullible people. The Royal Court then spoiled this by regretting that eight days was the maximum-possible sentence for witchcraft and that a heavier penalty could not be inflicted, before requesting HM Procureur to ask for an increase in the prison term for all such future crimes.

Overlooking the much more serious crime of demanding money with menaces, the Royal Court was, unbelievably, concerned that a few small bags of blancmange powder ‘full of little devils’ had been buried in someone’s garden at ‘cardinal points of the compass’.

Had the request to HM Procureur succeeded, all those who mixed anything with blancmange powder would be at risk of breaking the law and landing themselves in jail.

A Perspective on Guernsey at that time

The belief in witchcraft was still so strong at that time that it was even considered unlucky not to have ledges built into the chimney stack of a house. Here, passing witches could rest on their travels.

Guernsey, on the eve of the Great War, was an isolated, superstitious community which fervently believed in witches, werewolves, fairies and magic. The ‘power’ of ‘witch charms’ depends more on the beliefs of those using them than on anything else and similar ‘charms’ can still be found on sale in various New Age shops today.

You must be logged in to post a comment.