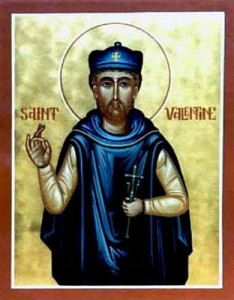

Monday 14th 270 AD was quite a day for Bishop Valentine of Interamna (now Terni in Umbria), for on that day, in Rome, he was stoned to death and then beheaded on the orders of Emperor Claudius II Gothicus.

Monday 14th 270 AD was quite a day for Bishop Valentine of Interamna (now Terni in Umbria), for on that day, in Rome, he was stoned to death and then beheaded on the orders of Emperor Claudius II Gothicus.

The reasons for the Emperor’s brutal command have become clouded with the passing of the centuries. (Indeed, there are even stories of two other Valentines, both improbably executed on 14 February.)

One story maintains that Claudius had outlawed marriage for young men, believing that bachelors without the encumbrance of families made better soldiers, but Bishop Valentine had continued secretly to perform weddings. Another account insists that Valentine had been arrested for converting Romans to Christianity (Claudius was a pagan). Whatever the true reason, Claudius ordered his execution.

But while Valentine was in prison he fell in love with the blind daughter of the jailer. Through his love for her and his Christian faith he restored her sight, and just before he was led away for execution he sent her a last letter signed ‘from your Valentine‘. And so the romantic legend of Valentine began.

A Christian Feast Day is Declared

Over two centuries later, in 496, another saint, Pope Gelasius I, declared 14 February a Christian feast day to honour him. But canny Gelasius was doing more than simply commemorating the martyrdom of a saint. At the end of the 5th century many people stubbornly hung on to a pagan celebration called Lupercalia, an ancient Roman fertility festival that took place each year on 15 February.

Lupercalia

During Lupercalia the priests, called Luperci, sacrificed a goat and a dog and then smeared the animals’ blood on the foreheads of two naked young men. The young men then put on loincloths and ran about the city gently striking young women with strips of hide from the sacrificed goats, thus ensuring the women’s fertility. Another feature of the Lupercalia was a lottery in which the names of nubile young girls were placed. Then each young man of the town drew lots to find the name of his lover for the duration of the festival.

Over the centuries Roman soldiers spread this festival throughout Europe, and even when Pope Gelasius substituted St Valentine’s Day for the Lupercalia, some of Lupercalia’s sexual celebration continued to be associated with the holiday.

Over the centuries Roman soldiers spread this festival throughout Europe, and even when Pope Gelasius substituted St Valentine’s Day for the Lupercalia, some of Lupercalia’s sexual celebration continued to be associated with the holiday.

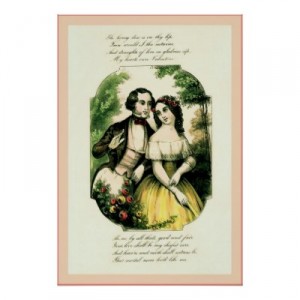

By happy coincidence, during the Middle Ages the tradition of finding a partner at Lupercalia/St Valentine’s Day was reinforced by an old folk belief that halfway through February birds find their mates. Some also claimed that Geoffrey Chaucer was the first to make this connection explicitly in his 1381 poem ‘Parliament of Foules’ honouring the engagement between England’s King Richard II and Anne of Bohemia:

For this was sent on Seynt Valentyne’s day

Whan every foul cometh ther to choose his mate

The First Valentine’s Cards

At about the same time it became the fashion for young men to give the women who attracted them billets doux mentioning St Valentine. It is said that in 1415 Charles, duc d’Orleans, who had been captured at the Battle of Agincourt and sent to the Tower of London, sent the first true Valentine card to his wife.

At about the same time it became the fashion for young men to give the women who attracted them billets doux mentioning St Valentine. It is said that in 1415 Charles, duc d’Orleans, who had been captured at the Battle of Agincourt and sent to the Tower of London, sent the first true Valentine card to his wife.

The tradition of sending Valentines took a big step forward in 1797 when an English publisher brought out The Young Mans Valentine Writer, a self-help manual for the lovelorn. Valentine’s cards became widespread in the United States only in the 1840s, when Esther Howland, a romantic Mount Holyoke graduate from Worcester, Massachusetts began mass-producing them.

Today millions of Valentines are sent each year, 85 per cent of them by women. Sadly, in 1969 Pope Paul VI dropped the Feast of St Valentine from the Catholic calendar, maintaining that the saint’s historical origins were highly suspect.