The Outbreak of the Civil War

In 1642 the English Civil War broke out after years of tension between Parliament, the King and his people. Whilst events on the ‘mainland’ may have seemed far away to the average Guernseyman, like every Englishman Guernsey found it had to choose a side. As in England choosing was never easy, families were torn apart with father against son, brother against brother. In the end Guernsey sided with Parliament whilst Guernsey’s Governor, Sir Peter Osbourne, chose the King. The Governor fled to Castle Cornet and thus began one of the strangest affairs of the Civil War a 9 year siege between the Castle, that was supposed to protect Guernsey’s main sea port, St Peter Port and the island of Guernsey itself.

The Royalist Cause

The King’s cause in Guernsey was supported by those who had a vested interest in the “Establishment”- landowners and those faithful to the Church of England. Most parish clergy by this time were Calvinist. Only a few islanders felt that the King’s authority was threatened by Parliament and that the symbol of his authority, the Governor, still had validity.

In Jersey the all-powerful Carteret family had provided the incumbent governor and was able to sway support for the King. In Guernsey no-one had this power, not even the de Sausmarez family, and the Royalists remained throughout the Civil War, largely a silent minority.

The Parliamentarian Cause

Physically and spiritually, Guernsey was well separated from mainland England. Islanders had long felt alienated from the causes of King and Country as represented by the Governor. Guernsey had lost valuable trade with Europe due to English wars. Furthermore, the Island was strong in Presbyterian and Calvinist sympathisers, whose interests were best represented by Parliament. In Guernsey, there was no family with the strength or prestige of the Carterets of Jersey to influence it. Most powerful of its worthies were the Jurats Peter de Beauvoir, Peter Carey, and James de Havilland. These three became Parliamentary Commissioners in 1643 after the outbreak of hostilities.

Early in 1643 the Parliamentary Commissioners for Guernsey ordered Island ties to the King be severed and that the Lieutenant Governor, Sir Peter Osborne, be apprehended. Osborne meanwhile fled to Castle Cornet, his official residence, and with a handful of royalist troops determined he would hold out for the king.

The Capture and Escape of the Jurats

In late 1643 the support of the people of Guernsey for Parliament was wavering, due to lack of protection for their trading vessels. An impassioned plea from the Parliamentarian Governor, the Earl of Warwick, stiffened their resolve, which was further strengthened in October by a Royalist plot to capture the Lieutenant Governor, Colonel Russell, and the three Parliamentary Commissioners for Guernsey.

The Jurats (and Parliamentary Commissioners) Peter de Beauvoir, Peter Carey and James de Havilland were enticed aboard a ship, the “George” of Dover, by its Captain, named Bowden, who claimed he had urgent matters from England to discuss. Once aboard, the three were received by Royalist naval officers who threatened punishment if they did not co-operate. Bowden intended sailing on to Jersey to similarly capture the Parliamentarian authorities there but Russell forestalled him by sending a boat ahead to warn them.

Meanwhile, Sir Peter Osborne, Governor of Castle Cornet, demanded that the prisoners be handed over to him as hostages. Bowden refused, having been promised a bribe by the Commissioners to land them in England.

Osborne sent a force of men to remove the prisoners into Castle Cornet where they were lodged in a deep dungeon. The next day, they were moved into a room above, the contents of which, comprising old wet musket match, was put into their old quarters. Now at least, the prisoners had a small window to look out of.

On 23rd November 1643, after several weeks, the prisoners began cutting a hole through the floor with their knives to get at the match. A week later they had it, and were able to fashion three ropes – one to lower themselves down from the dungeon window, a second to drop them down an inner wall, and the third to get them over the outer wall onto the rocks below.

On Sunday 3rd December, with a Spring Tide leaving the causeway to the Town dry, and after being imprisoned for forty-three days, the Commissioners made their escape. They were detected on the causeway and shot at, after several misfires, which allowed them time to get away. The three appeared in St. Peter Port as the congregation was leaving church, and the news of their escape was quickly broadcast.

Their esacpe was not a moment to late as Osborne, it seems, had just received a Royal writ ordering their execution.

Castle Cornet’s Nine Year Siege

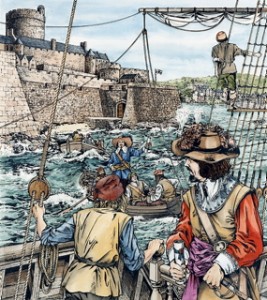

After the order in early in 1643 by the Parliamentary Commissioners to apprehend the Lieutenant Governor, Sir Peter Osborne, to seize all fortresses and to hold the Bailiwick for Parliament, Osborne retired to Castle Cornet, his official residence, and with a handful of troops (probably about 60) and prepared to hold the Castle. During a half-hearted attack on the Castle on Thursday 29 February 1643, at least six English soldiers and one Guernseyman were killed. In retaliation Osborne threatened to bombard St. Peter Port. He fired a few guns and many of the residents evacuated the town.

Parliament, wanting the Castle intact, held back from bombarding it, preferring to starve out the garrison by cutting off supplies. However the Castle continued to be supplied by sea, most notably from Royalist Jersey.

By 1644 the siege had a routine. Osborne would be regularly summoned to yield both the Castle and himself. He would refuse. Every few months Osborne would contact Col. Carteret, the Governor of Jersey, and the English Royalists to plan the taking of Guernsey. The inhabitants would become alarmed and warships would be sent for. The ships would stand off for a while then go away. If the Royalists sent supply vessels they would be fired on as they unloaded. The Castle would reply by firing on the Town.

No serious attempt was ever made to take the Castle, and two mismanaged attacks by the Parliamentarians were easily repulsed. Some damage was however, inflicted on the Castle walls by gunfire from town. St. Peter Port, in return suffered heavily from the Castle’s guns. Peter Osborne was replaced by Sir Baldwin Wake in May 1646. Wake gave up the Castle in despair in May 1649 and absented himself without leave. He was replaced in October 1649 by Col. Roger Burgess from Jersey.

In March 1651 an attack by the Militia on Castle Cornet was beaten off, with over thirty of the attacking force killed. With Charles I’s defeat at Worcester in Autumn 1651 the Royalist cause on the mainland foundered. One by one the Royalist garrisons including Jersey, surrendered, until only Castle Cornet held out. With command of the sea held by the Parliamentarian Navy, supplies to the Castle were cut off. Finally on 19th December 1651 the little band of defenders, only about 50 strong, was allowed to march out having received extremely favourable terms for the surrender of the Castle.

Even after the war was over and the Monarchy restored in 1660 after the brief period of the Commonwealth ruled over by the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell (1649-1660), Castle Cornet’s part in this great upheaval was not over. Because of its remoteness from England, Major-General Sir John Lambert, seen by many as the successor to Cromwell as Lord Protector, was imprisoned in the Castle from 1661 to 1670.

[Read more about Castel Cornet’s most famous prisoner – General Lambert]

You must be logged in to post a comment.