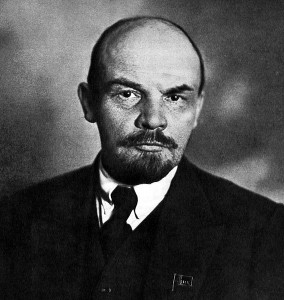

The great communist experiment that started in 1917 after the Bolshevist revolution in Russia ultimately failed with the fall of the Soviet Union in the nineties, trumped by the capitalist west. But was it ever given a fair go? Many would argue that is was hijacked by the ruthless oportunist Stalin after the death of Lenin. One can only speculate that had he lived whether communism could have been survived. In this article we look at the events that surrounded his death in 1924.

The Great Lenin is Felled

Sunday the 21st January 1924 Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was finally felled by a massive stroke. Already partially paralysed, bedridden and unable to speak, that morning at his villa in the village of Gorky, Communist Russia’s ruthless and implacable leader Vladimir Ilich Lenin suffered his fourth stroke in twenty months. At 5.50 that evening he died at the age of 53.

Sunday the 21st January 1924 Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was finally felled by a massive stroke. Already partially paralysed, bedridden and unable to speak, that morning at his villa in the village of Gorky, Communist Russia’s ruthless and implacable leader Vladimir Ilich Lenin suffered his fourth stroke in twenty months. At 5.50 that evening he died at the age of 53.

No horny-handed son of toil, Lenin was born to an inspector of schools and was an inspired intellectual who spoke four languages. But he focused his brilliance on what he saw as the intolerable inequities of tsarist Russia. More than any other man, he established what he called

‘the great experiment, the dictatorship of the proletariat’.

An Earlier Assasination Attempt

Ironically, Lenin’s early death may have been brought on by the attack not of a tsarist counter-revolutionary but of a fellow radical. In November 1917 the Congress of Soviets had elected Lenin chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars, in effect the most powerful man in Russia. Only months later he had peremptorily ordered the dissolution of the democratically elected Constituent Assembly in order to guarantee Bolshevik supremacy. The following August a disgruntled Socialist Revolutionary named Fanya Kaplan fired three shots at him as he headed for his car after a meeting, hitting him in the lung and at the base of his neck.

Fearing another assassination attempt, Lenin insisted on being taken to his own apartment rather than the hospital. There his doctors decided that it was too dangerous to remove the bullets, as one was lodged too close to his spine. In the meantime Kaplan was arrested, interrogated and, four days later, shot.

Lenin seemed to recover from his wounds, but from that time his health, already under the intolerable strains of revolution and war, started to deteriorate. Four years later he became so ill that in April 1922 the bullet from his neck finally had to be removed. Only a month later he suffered his first stroke, which left him paralysed on his right side.

A second stroke followed in December, leaving him bedridden, and in March a third stroke deprived him of speech. Ten months later his fourth and final stroke finished him off.

A second stroke followed in December, leaving him bedridden, and in March a third stroke deprived him of speech. Ten months later his fourth and final stroke finished him off.

Three days after his death Petrograd was renamed Leningrad, and at his funeral, Lenin’s corpse was swathed in a red flag saved from the Paris Commune of 1871. Four days after that, his mummified body went on display in the Lenin Mausoleum in Moscow’s Red Square, but before his embalmment, his brain was removed so that it could be studied to identify the precise location of the cells responsible for his revolutionary genius.

Rumours Around is Death

Despite the adulatory theatrics of a grieving Communist Party, only weeks after Lenin’s death rumours began to circulate that the real cause of his demise was not a stroke at all but syphilis. It was thought that he had contracted the disease as early as 1895, and in 1923 he had been treated with potassium iodide and a drug called Salvarsan, which were used at the time against syphilis. It was also said that the pathologist in charge of his autopsy had been ordered not to mention syphilis, and any syphilis-related indications were expunged from his report.