The English Civil War was a complex affair. Even today historians are unable to completely agree on the exact causes of it. Loyalties and families were divided, brother against brother father against son. Men even changed sides. So to capture or explain this 9 year conflict in one small article would be impossible. Instead here we simply restrict ourselves by looking at some simple notes and observations on this tumultuous and seminal conflict that gave the British the democracy and constitutional monarchy they still enjoy today.

The English Civil War : 1642-1651

The Outbreak of War

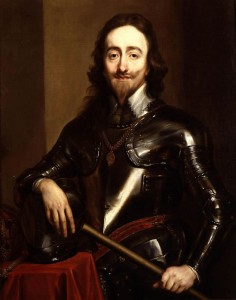

The Civil War in England broke out in in August 1642. On one side stood King Charles I, and his supporters and on the other, men like Oliver Cromwell who believed that the king was a tyrant. War spread to Scotland, Ireland and Wales and lasted nearly nine years. Families and friends found themselves on opposite sides but were prepared to fight each other to the death.

Historians still disagree about why war broke out but the following certainly played a part:

Government – Charles I believed that God had made him a king and that he had no need to consult Parliament so he ruled without it from 1629 to 1640. This led to a power struggle between him and the Members of Parliament.

Religion – England was a Protestant country but Charles I introduced ceremonials and rituals that teemed very Roman Catholic to a lot of people. Those that feared this, fought against the king.

Cromwell’s War

King Charles raised his standard on 22nd August 1642, declaring war, Oliver Cromwell was made a captain and spent the autumn raising a troop of about sixty horsemen from this area then in October they joined the main army of Parliament. In 1643, Cromwell was made a colonel and put at the head of a cavalry regiment within the Eastern Association, Parliament’s army in East Anglia. For much of the war, he was engaged in almost continuous military service and was hardly ever at home in Ely, He became extremely successful and played a crucial part in some of Parliament’s most important victories.

The New Model Army

At the start of the war both the King and Parliament relied on private armies being raised by wealthy men to fight in their local area as Cromwell had done in East Anglia. This situation changed in 1645 when Parliament realised that it needed a more organised national army if it was going to defeat the king. The New Model Army, the forerunner of today’s professional army was created with Sir Thomas Fairfax in command. Parliament also voted that Members of Parliament, including Oliver Cromwell, should cease to be soldiers and leave the command of the army to professionals. Fairfax, recognising Cromwell’s military genius asked him to be his second- in-command and from that point on Parliament kept on extending his commission so that Cromwell could fight. In 1646 the New Model Army shattered the king’s forces at the Battle of Naseby, a defeat from which he never recovered.

The Execution of the King and The Commonwealth

King Charles’ army had suffered a total defeat but once captured, he refused to negotiate. Parliament’s frustration with him grew when he escaped and arranged a deal with the Scots who gave him an Army to invade England with. It was defeated quickly and the king was put on trial for treason. He was found guilty and beheaded at Whitehall in London in January 1649.

England was now a Commonwealth, ruled by Parliament alone. What was left of the Parliament elected in 1640 ran the country but in April 1653 Cromwell and the Army dismissed this Rump Parliament for being ineffective. A Nominated Assembly was set up in its place but this soon became locked in a stale-mate because its members couldn’t agree. In December the majority signed its powers back to Cromwell. He seemed to be the only authority left so on December 16th 1653 Oliver Cromwell was made Lord Protector, the Head of State.

Ireland

In 1649 a rebellion broke out in Ireland led by Roman Catholics who supported the king. Cromwell was sent by Parliament at the head of an army to end the uprising. He spent nine months there and was successful but he has been criticised for his methods. At Drogheda in September 1649 the people occupying the town refused to surrender and when Cromwell’s men took the town they killed nearly all of the 3,100 soldiers that they found there and several hundred townspeople. At Wexford in October, the commander of the castle surrendered but when some of his soldiers and townspeople resisted around 2,000 people were killed.

Some historians have judged this as a brutal act but others stress that it was typical of the time and the violent animosity between the English and the Irish. In 1641-42 for example several thousand Protestants had been killed by Irish Roman Catholics.

Oliver Cromwell – Hero or Villain?

So was Oliver Cromwell a champion of liberty or a tyrant who wanted power for himself? Here are some of the things that he did – you decide!

![]() Head of State as part of a written constitution voted by Parliament

Head of State as part of a written constitution voted by Parliament

![]() One of the people who signed the death warrant of King Charles I

One of the people who signed the death warrant of King Charles I

![]() Allowed the Jews back into England

Allowed the Jews back into England

![]() Brought back the state censorship that Charles I had operated

Brought back the state censorship that Charles I had operated

![]() Imprisoned and exiled his opponents without trial as previous monarchs had

Imprisoned and exiled his opponents without trial as previous monarchs had

![]() Advocated freedom of belief for all Protestants, regardless of their sect

Advocated freedom of belief for all Protestants, regardless of their sect

![]() Put down rebellions in Ireland with great severity

Put down rebellions in Ireland with great severity

![]() Led a strong and respected foreign policy

Led a strong and respected foreign policy

![]() Led a peaceful regime that began to heal the wounds of the war and unite very different opinions

Led a peaceful regime that began to heal the wounds of the war and unite very different opinions

You must be logged in to post a comment.