a word derived from the name of a real, fictional or mythical character or person after whom a discovery, invention, place, etc., is named or thought to be named.

Eponyms are one of the most fascinating examples of how the English language gains new words. In this article we take a colourful look at the phenomenon that is the eponym gathering together the stories of the people behind the words that have passed into our everyday vocabulary.

JUGGERNAUT

The proverbial irresistible force, the name has been used for massive trucks and tanks, large ships and at least two movies featuring murderers who seemingly can’t be stopped.

Yet the original Juggernaut was nothing more than an image of the Hindu god Vishnu, one of whose titles is ‘Jagganath’, meaning Lord of the World. It was a very large image, carried on huge carts from the temple in Puri, India, and, according to scurrilous European reports, people would throw themselves in front of the cart to gain martyrdom. Not actually true, as the real problem was the sheer size of the Jagganath in close proximity to excited crowds. But it made for good gossip in the days of the Raj, and Jagganath was soon translated to ‘Juggernaut’, being applied to vehicles that just kept growing.

Yet the original Juggernaut was nothing more than an image of the Hindu god Vishnu, one of whose titles is ‘Jagganath’, meaning Lord of the World. It was a very large image, carried on huge carts from the temple in Puri, India, and, according to scurrilous European reports, people would throw themselves in front of the cart to gain martyrdom. Not actually true, as the real problem was the sheer size of the Jagganath in close proximity to excited crowds. But it made for good gossip in the days of the Raj, and Jagganath was soon translated to ‘Juggernaut’, being applied to vehicles that just kept growing.

The journey from Hindu god to 40-tonne truck is another example of how eponyms develop, and it’s certainly one of the more bizarre derivations.

LYNCHING

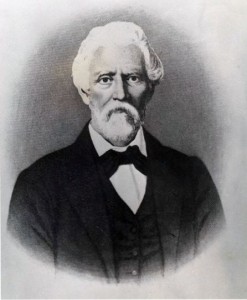

One of those hotly disputed eponyms, the word for a mob’s revenge killing of a guilty or innocent person is usually said to come from Charles Lynch (1736-96), an American patriot from Virginia who became a militia colonel in the battle against the British in the War of Independence. A former Quaker, Lynch became a justice of the peace and used the office to begin what he himself called ‘Lynch Law’, in which he and his colleagues terrorised those residents of Virginia who sided with the British.

Trials were a mere irritation to Lynch as he handed out sentences ranging from forced conscription to whipping. He never actually ‘lynched’ anyone – i.e. hanged them from a tree – but that was soon a common occurrence in the USA, as the deep south in particular saw lynch mobs, often organised by the Ku Klux Klan, hang many more black people than white without resorting to the justice system.

Other Lynches in America and Ireland have been claimed as the original ‘lynch’, but Charles has by far the best provenance.

MALAPROPISM

A malapropism is an accidental or deliberate witticism created by using a wrong word, especially one that sounds or looks like the word that was originally intended to be used.

A malapropism is an accidental or deliberate witticism created by using a wrong word, especially one that sounds or looks like the word that was originally intended to be used.

The best malapropisms are always the accidental ones – but the originator of the term deliberately coined malapropisms for intentional comic effect. Richard Brinsley Sheridan created the character Mrs Malaprop in his 1775 play The Rivals, productions of which take place to this day. No wonder, as the play is very funny with Mrs Malaprop providing some of the most hilarious moments with her mangling of the language.

Among her gaffes are :‘he is the very pineapple [pinnacle] of politeness’

‘he’s as headstrong as an allegory [alligator] on the banks of the Nile’.

Malapropisms were not new in 1775. Shakespeare abounds with them, particularly Dogberry in Much Ado about Nothing. They have long been a staple of comedy in books, films and television shows

President George W Bush frequently ‘mis-spoke’ as he put it – ‘the illiteracy of our children are [is] appalling …’ – but these Bushisms were not true malapropisms, just garbled speech, though he did once say he had been ‘pillared [pilloried] by the press’.

MAVERICK

There are, no doubt, some people who think we get the word ‘maverick’ from the American television Western series of that name which made a star of the much underrated James Garner. They are not completely wrong, because the word derives from a heroic figure of the Old West, Samuel Augustus Maverick, who was not a gambler but a lawyer who kept some cattle on the side.

Confusingly, there is another prominent Samuel Maverick in American history, but he was a 17th-century English colonist in Massachusetts and has no connection to the word.

Born in 1803 in South Carolina, Sam Maverick moved to Texas with his young wife Mary. We know a great deal about them, principally because Sam wrote a journal, Mary kept a diary and his son George also wrote about him, all of these accounts being later published.

Born in 1803 in South Carolina, Sam Maverick moved to Texas with his young wife Mary. We know a great deal about them, principally because Sam wrote a journal, Mary kept a diary and his son George also wrote about him, all of these accounts being later published.

His father’s success in business meant that Sam Maverick could buy a lot of land in Texas, which was then part of Mexico. He then became involved in the revolution which led to the Texan Declaration of Independence, and was imprisoned by the Mexicans for his stance.

Having acquired 400 head of cattle in payment for a debt, Maverick seems genuinely not to have cared about what happened to his animals, which were left to roam about the area. Unbranded cattle in Texas thus became known as ‘mavericks’ and the word soon spread, coming to mean a person who refused to conform and which is now used in the sense of wild and unpredictable.

Maverick County in Texas is also named after him.

TANTALISE

This alluring word for teasing and titillating comes from Tantalus, a figure from Greek mythology who, tantalisingly, may have been based on a real person.

This alluring word for teasing and titillating comes from Tantalus, a figure from Greek mythology who, tantalisingly, may have been based on a real person.

Supposedly the King of Anatolia or Phrygia (in modern-day Turkey), Tantalus departed history and entered mythology by angering the gods – he served them a feast made from the chopped-up body of his own son. He may also have stolen the food and drink of the gods, ambrosia and nectar, and given them to mortals.

Whatever he did, the gods of Olympus were not pleased and, as a result, he was banished to the Underworld and condemned to stand in a lake for ever. Every time he reached up to grab fruit from an overhanging tree, the branch withdrew and every time he bent to drink from the lake, the water shrank away from him, so that he spent eternity just out of reach of sustenance.