There are some events in history upon which turn the fate of nations. A point at which history can go either way. In this article we look, very briefly, at four of, what we think of at least, are key battles in the life and evolution of Great Britain. Battles which have played a part in defining what Britain is, from the Norman invasion of 1066 to the vast set-pieces of the Second World War. Who can fail to be stirred by the story of Henry V’s victory at Agincourt or made proud by the memory of the fighter pilots of the Battle of Britain, the ‘few’ made legend by Winston Churchill’s famous speech?

HASTINGS, 1066

This first Great British Battle was also the last on British soil in which a foreign power won. William, Duke of Normandy was a 39-year-old warrior leader in 1066, flush with his success in securing Normandy against the threats of the French King Henry I. An invasion of the island just across the sea from his home, to which he had a tenuous claim on the throne, was the logical next step.

Harold, the English king, was himself basking in wartime victory: his army had just defeated invasion in Yorkshire from the Norwegian Harald Hardrada, another foreigner with his own claim to the English throne, at the Battle of Stamford Bridge.

On 28 September 1066, around 7,000 Normans arrived on the Sussex coast. The decisive battle itself was fought not in Hastings but some 5 miles (8km) inland, at the place now helpfully called Battle.

Things didn’t start well for William, and when his horse was killed underneath him. the Norman army feared their leader dead. William had survived, however – he stood up. threw off his helmet and rallied his knights and troops for a bloody counter-attack.

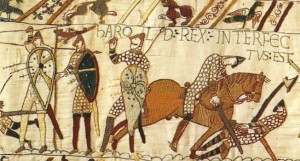

The clash of armies was immortalised in one of the most intricate and fascinating historical records of all time, the Bayeux Tapestry. Its most famous scene records the death of the defending king, Harold, struck in the eye by an archer’s arrow.

Following the battle, William marched on London and was soon crowned William I: William the Conqueror. The Normans then consolidated their victory, with thousands of Norman families moving across the channel to settle in Britain – if you’re British then it’s very likely that you’re a descendant of one of them.

AGINCOURT, 1415

As Hastings was immortalised by the Bayeux Tapestry, Henry V’s showdown battle with the French at Agincourt was made myth by Shakespeare. The Bard has the king rally his troops with a stirring speech, the most famous phrases of which would be heard again from the mouths of beleaguered British leaders in times of wartime peril:

“We few, we happy few, we band of brothers”, Henry proclaims.

Shakespeare, of course, was writing fiction, but the victory at Agincourt has come to stand for the British underdog spirit. Henrv V had invaded France in August 1415, pursuing his claim to the French throne. By 25 October, St Crispin’s Day, his army had reached Agincourt, about 20 miles (32km) south-east of modern-day Boulogne. The odds were firmly stacked against Henry, with as many as five French soldiers for every Englishman.

Shakespeare, of course, was writing fiction, but the victory at Agincourt has come to stand for the British underdog spirit. Henrv V had invaded France in August 1415, pursuing his claim to the French throne. By 25 October, St Crispin’s Day, his army had reached Agincourt, about 20 miles (32km) south-east of modern-day Boulogne. The odds were firmly stacked against Henry, with as many as five French soldiers for every Englishman.

Taking particular advantage of the woodland around the battlefield and the longbowmen – archers – who made up as much as 70 per cent of his total force, and fighting in hand-to-hand combat himself, Henry secured a famous English victory, a milestone in what became known as the Hundred Years War. Henry’s reputation even seems to have survived his brutal order to massacre several thousand French prisoners he feared were massing for a counter-attack.

THE SPANISH ARMADA, 1588

This is the story of a battle that, fortunately for the British, never quite was.

This is the story of a battle that, fortunately for the British, never quite was.

One quiet July day on the rugged peninsula of the Lizard in Cornwall, a flotilla of ships was spotted on the horizon. The Spanish were here, a few miles from the coast-and hell-bent on invasion. King Philip of Spain had been, with Queen Elizabeth I’s sister Mary, England’s co-monarch until Mary’s death in 1558. A devout Catholic, he considered Elizabeth, a Protestant, an illegitimate ruler and would do anything he could to usurp her from the throne.

After the sighting in Cornwall the Armada made its way through the English Channel – the intention being to make port in Flanders and join with the Duke of Parma for an invasion of the south-east coast. But this never happened – the Armada was harried all the way round the British Isles by Sir Francis Drake among others, and thanks too to severe storms off of Scotland’s west coast, returned to Spain with its strength hugely depleted (50 ships were lost, of 130 that made up the Armada in the beginning). The invasion plans were shelved.

WATERLOO, 1815

“The nearest-run thing you ever saw in your life” was Lord Wellington’s famous verdict on the Battle of Waterloo – hardly a ringing endorsement of a great British victory. But a great victory it was – even if only 24,000 of the 68,00 strong victorious army were in fact British.

“The nearest-run thing you ever saw in your life” was Lord Wellington’s famous verdict on the Battle of Waterloo – hardly a ringing endorsement of a great British victory. But a great victory it was – even if only 24,000 of the 68,00 strong victorious army were in fact British.

Wellington was in retreat after France’s dictatorial military overlord, Emperor Napoleon I, had invaded Belgium and defeated Wellington’s Prussian allies. The retreat paused on the road to Brussels by the small town of Waterloo.

The nearest-run thing you ever saw in your life

The battle opened a 11:00 am with the French bombarding Hougoumont Farm, on the extreme right of the Allied line, and it raged furiously through the day, the tide of battle shifting first one way and then the other. But the tactical genius that had characterised Napoleon as a commander earlier in his career seems to have deserted him and, after a strong defence by Wellington and the arrival of Prussian reinforcements, the French army was soundly routed. At last, France was crushed and the stage was set for the British empire to grow and prosper, without fear of French (or much other) resistance throughout the 19th century.

You must be logged in to post a comment.