Do you really need your Brain ? : WHAT !? … A joke surely. No, this is a serious question (sort of).

To see why we might ask it though we need to look at a rather strange phenomenon first observed in the 1980s.

A Strange Phenomenon

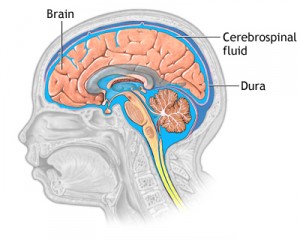

In the 1980s a British neurologist, John Lorder, reported on a number of cases of people who appeared to have heads that were largely empty, apart from what is called cerebrospina fluid, a clear bodily fluid in which the normal brain floats. This fluid is like a shock absorber, protecting the brain from damage if the head is knocked. He made his discovery after a student at the university where he worked was referred to him for having a slightly larger than normal head. Using an early type of brain scan, Lorber found that where a normal scan would show brain tissue filling the entire volume of the head, this man, in Lorber’s words, had “virtually no brain”. This was one of the most dramatic of Lorber’s discoveries in an investigation that revealed a number of similar examples of people who possessed merely a thin layer of brain cells just underneath the skull, with the rest of the head being fluid. In effect, they had brains that had as little as 5 per cent of the volume of normal brains.

Of course, in the history of illness and pathology there are many sad stories of people with serious deficits, usually leading to major disabilities. But the astonishing thing about the people Lorber reported on was that many of them were leading perfectly normal lives, in which they raised a family, held good jobs and indeed were unaware that their own heads contained very little brain matter. Some were even chartered accountants.

The people concerned had had hydrocephalus when they were children. This is a condition in which the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid around the brain and spinal cord is blocked and so there is a slow build-up of pressure in the brain, which pushes the brain cells outwards against the inside of the skull, like an inflated balloon.

Some of the people to whom this happened are severely disabled, but for reasons that no one can explain, about half of them seemed to have normal intelligence with IQs of 100 (the average in the population) and above. Lorber’s work was reported in the 1980s, and some scientists were suspicious of the research. ‘Most neurologists don’t perform brain scans just because a college student wears a large hat,’ said one. But over the years similar cases have been discovered. In 2007, the magazine Wired reported ‘Brain not necessary for French civil service worker’, over a story of a forty-four-year-old Frenchman who went to the doctor because he had mild weakness in one leg, and was discovered to have greatly reduced brain tissue, about 25 per cent of normal, as a result of hydrocephalus when a child. Nevertheless, he was a married man with two children and had a regular job as a civil servant.

How is this possible ?

The key to understanding how brain tissue can still function under such extreme conditions is the slowness with which the pressure of the cerebrospinal fluid changes the brain’s size and structure. No one is suggesting that, at a stroke – so to speak – we can all manage with a quarter or less of our own brain tissue. But somehow the brains of these unusual people have managed to adapt gradually with each small increment of pressure, so that as some parts of the brain were being pushed aside, their functions were taken over by other parts.

Intriguing as these cases are, the answer to the question ‘Is your brain really necessary?’ is ‘yes’. Someone whose brain is only 10 per cent of its original mass still has about ten billion brain cells. While a proportion of our brain cells are necessary to live a normal, reasonably stable life, there are many other brain functions we are not aware of and, perhaps, don’t use most of the time, but which come to the fore in emergencies, in rapidly changing circumstances or to access information we may need once every ten years. The evidence that one can maintain a normal family life and hold down a job is evidence only of some brain activity, rather than the optimum that a fully normal brain can achieve.

You must be logged in to post a comment.