We have probably all had this experience. We listen to a recording of ourselves talking and insist that the tape doesn’t sound at all like our voice, but everyone else’s sounds reasonably accurate. “Au contraire,” the other listeners will retort (especially if they’re French), “Yours sounds right”.

We have probably all had this experience. We listen to a recording of ourselves talking and insist that the tape doesn’t sound at all like our voice, but everyone else’s sounds reasonably accurate. “Au contraire,” the other listeners will retort (especially if they’re French), “Yours sounds right”.

According to speech therapists there’s a pretty universal pattern of rejection of one’s own voice.

So, is there a medical explanation for this lack of self-perception : Yes – there is…

Speech begins at the larynx, where the vibration emanates. Part of the vibration is conducted through the air—this is what your friends (and any recording device) hears when you speak. However another part of the vibration is directed through the fluids and solids of the head.

Speech begins at the larynx, where the vibration emanates. Part of the vibration is conducted through the air—this is what your friends (and any recording device) hears when you speak. However another part of the vibration is directed through the fluids and solids of the head.

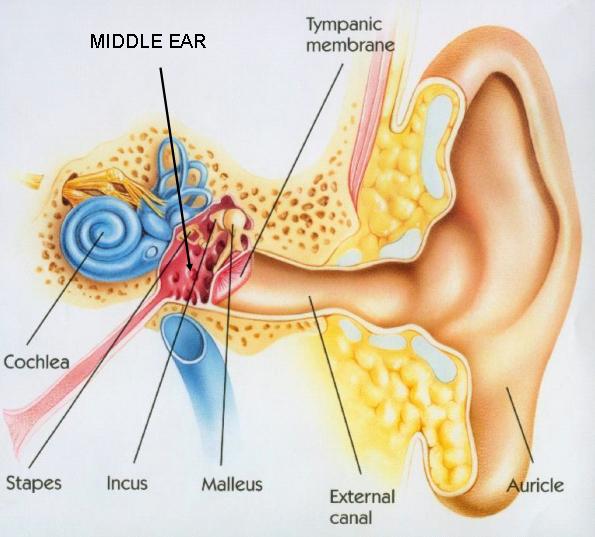

Our inner and middle ears are parts of caverns hollowed out by bone—the hardest bone of the skull. The inner ear contains fluid; the middle ear contains air; and the two are constantly pressing against each other. The larynx is also surrounded by soft tissue full of liquid. Sound transmits differently through the air than through solids and liquids, and this difference accounts for almost all of the tonal differences we hear when reacting negatively to our own voice on a recorder.

When we listen to our own voice while we speak, we are not hearing solely with our ears, but also through internal hearing, a mostly liquid transmission through a series of bodily organs.

Consider this – during an electric guitar solo, who hears the “real” sound? The audience, listening to amplified, distorted sound? The guitarist, hearing a combination of the distortion and the pre-distorted sound? Or would a recorder located inside the guitar itself hear the “real” music? The question is moot. There are 3 different sounds being made by the guitarist at any one time, and the principle is the same for the human voice.

We can’t say that either the voice recorder or the speaker hears the “right” voice, only that the voices are indeed different.

In addition it should also be noted that we have an internal memory of our voice in our brain, and the memory is invariably richer than what we hear on any recorder playback. Although there seems to be no consistent pattern in whether folks hear their voices as lower or higher pitched than other listeners, there is no doubt that internal hearing is of much higher fidelity than external hearing. Listening to our own voice on a recorder is like listening to a favourite symphony on a bad transistor radio — the sound is recognizable but a pale imitation of the real thing.