Origins

St Nicholas is acknowledged as the ‘original Santa Claus’. However very little is known about him for certain; indeed, his very existence has sometimes been called into question. All that can be said with any degree of confidence is that St Nicholas probably lived in the fourth-century in the Lycian port of Myra, in the south-west of modern Turkey, and that he was a bishop. In addition, it is likely that he died on the 6 December, which was celebrated as his feast day in the medieval church calendar; later accounts also add that St Nicholas attended the Council of Nicaea and was vocal in opposing the Arian heresy, which does not seem implausible. One of the earliest legends that was attached to his name tells how St Nicholas heard of a man who could not afford the dowries for his three daughters, with the result that he intended – regretfully – to send them to the brothel to work. St Nicholas saves them from this fate by throwing three bags of gold through their window at night: it is this tale which is often identified as the root of St Nicholas’s reputation as a gift-giver.

Evolution

Over the course of the medieval period the legend of St Nicholas continued to develop and spread enormously. In addition to becoming the patron of sailors as part of this process, St Nicholas also became known as the patron of children. This combined with his reputation as a gift-giver, all the key elements were in place for the transformation of St Nicholas into the modern giver-of-gifts to children. The most significant manifestation of this, from the perspective of Santa Claus, is the Dutch Sinterklaas. Whilst Sinterklaas clearly derives from St Nicholas and his feast-day of the 6 December, he differs from the earlier portraits of St Nicholas in a number of ways, not least in his flying white horse. These differences are usually explained as a result of the legends of St Nicholas being fused in the medieval period with those of the former pagan god Wodan (the Norse Odin, who did possess a flying horse named Sleipnir), although one does have to wonder whether all of the aspects of the legend of Sinterklaas which are sometimes claimed to derive from this fusion really do so. Whatever the case may be, in the Early Modern era there were several unsuccessful attempts to stamp out the Sinterklaas tradition for religious reasons; more recently it has been attacked as a ‘racialized tradition’, due to Sinterklaas’ companion Black Pete, but it remains nonetheless popular in Holland.

The American Santa Claus

The American Santa Claus is generally considered to have been the invention of Washington Irving and other early nineteenth-century New Yorkers, who wished to create a benign figure that might help calm down riotous Christmas celebrations and refocus them on the family. This new Santa Claus seems to have been largely inspired by the Dutch tradition of a gift-giving Sinterklaas, but it always was divergent from this tradition and was increasingly so over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. So, the American Santa is a largely secular visitor who arrives at Christmas, not the 6 December; who dresses in furs rather than a version of bishop’s robes; who is rotund rather than thin; and who has a team of flying reindeer rather than a flying horse. At first his image was somewhat variable, but Thomas Nast’s illustrations for Harper’s Illustrated Weekly (1863-6) helped establish a figure who looks fairly close to the modern Santa. This figure was taken up by various advertisers, including Coca-Cola, with the result that he is now the ‘standard’ version of the Christmas visitor and has largely replaced the traditional Father Christmas in England.

The English Father Christmas

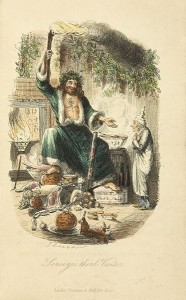

Scrooge's third visitor (wearing green) in Dickens's A Christmas Carol, a Victorian representation of Father Christmas

The English Father Christmas seems to have had an entirely separate origin from Sinterklaas, being a personification of Christmas and a Yule-tide visitor – not a gift-giver – rather than a version of St Nicholas. The earliest reference to him comes from the mid-fifteenth century, when a Sir Christëmas appears in a carol. In the nineteenth century Father Christmas benefitted from the general Victorian revival of Christmas and can be found in, for example, Dickens’ Christmas Carol. However, from the 1870s onwards Father Christmas became increasingly like the American Santa Claus, both in terms of his actions – he started giving gifts – and his appearance, with the result that two are nowadays virtually inter-changeable.

You must be logged in to post a comment.