Discovery and introduction to Europe

After 20 years travelling all over Asia, merchant Marco Polo returned home to Venice laden with wares to trade and ideas to share. However in 1298, Venice was at war with Genoa and Polo got caught up in the middle of it. In the Battle of Curzola, he was captured and locked up for several months. While in prison, he recounted his travels through Asia to fellow cell mate Rustichello da Pisa, a skilful penman.

When the Venetians were finally released, Rustichello wrote about his cell mate’s adventures in “The Travels of Marco Polo”, recounting stories of Polo’s reputed life in the court of the Mongol leader Kublai Khan and also the existence of things such as paper money. However crucially the book omitted a number of key details from Chinese culture – the practice of foot-binding, eating with chopsticks and drinking tea – none of which existed in Europe at the time. It also didn’t mention the difference between the Chinese script and Roman alphabet, nor did it talk of the technique of woodblock printing, which the Chinese had been doing for centuries. For some scholars these ommissions call into question the authenticity of Polo’s claims to have travelled as far as he did.

As far back as the third century ad, carved blocks of wood were used by the Chinese to print patterns on fabric. Pi Cheng is credited with inventing movable wooden type in 1045, where one face of a block of wood was carved by hand to leave a raised character. By the thirteenth century, people in Korea started placing a layer of metal on to the characters to make them more durable. The thousands of ideographs in the Chinese language meant the process of printing was complex. What was needed was a language with fewer characters.

Legend has it that, although printing was never mentioned in “The Travels of Marco Polo”, the merchant realised how much simpler woodblock printing would be if the Roman alphabet with its limited number of characters were used, and so, reportedly, he introduced the idea to Europe.

For the next couple of centuries, everything from books to playing cards were printed using the laborious woodblock method. Then, in 1440, the son of a rich German merchant revealed a groundbreaking invention that he’d been working on in secret for years.

Printing Revolution

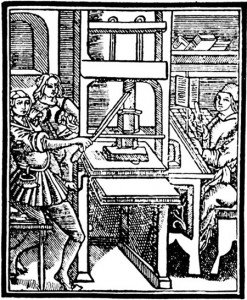

Johannes Gutenberg was preparing for showcasing polished metal mirrors that he and colleagues had created for an exhibition in the German city of Aachen in 1439. At the last minute, the exhibition was cancelled and the investors came knocking. Instead of stumping up the cash to get the investors off his back, he promised to share with them the secret invention that he’d been working on.

Reportedly, the invention Gutenberg revealed was his printing press – a wooden machine which combined the idea of block printing with the technology used in a screw press for making olive oil and wine. Paper, mounted on a flat board called a ‘tympan’, was pressed down onto another flat board, a ‘forme’, which held inked type securely in place. The individual letters of the type were made by pouring the elements lead, tin and antimony into copper moulds, so the letters were quicker to make and more durable than hand-carved wooden ones.

The device completely changed the face of printing. It could produce as much material in one day as a scribe could produce in one year. Rather arrogantly, Gutenberg said of his invention: “Like a new star, it shall scatter the darkness of ignorance.” But he was right: by the end of the sixteenth century, 150 million books had been published across Europe.

The Bible was one of the first books Gutenberg produced, and initially it dominated the book market. Gradually other texts became available, including science books such as Copernicus’s “De Revolutionibus”. Where once the printed word had been the domain of the wealthy and the clergy, Gutenberg’s printing press opened up a new world to the literate.

For those living at the time, the invention of the printing press must have been like the invention of the internet during the late 20th century, Suddenly a vast body of information became accessible – albeit to those who were literate. But that didn’t matter because, just like the internet has encouraged people to be savvy with computers, so the printing press and the easy availability of literature that it brought fostered education and encouraged people to read and write.

Speed Printing

A faster press meant cheaper books, so people were always on the lookout for ways to improve the machine. In 1811, German inventor Friedrich Koenig and Andreas Bauer demonstrated their high-speed press driven by steam, which could print more than 15 pages a minute.

Three years later, on 29 November 1814, The Times was the first newspaper to be printed on it.

Half a century on, clockmaker Ottmar Mergenthaler was asked by venture capitalist James Clephane and colleague Charles Moore to find an even quicker way to print legal documents. Mergenthaler realised that operators didn’t need to place each precast metal letter one by one, but instead metallic letter moulds could be assembled in a long line. An operator then pressed buttons specific to certain letters to select whichever ones were required. These letters were then cast as a single piece of metal, known as a ‘slug’.

This Linotype machine – ‘line-o’-type’ – speeded up the printing process dramatically. Before 1886, no newspaper had more than 8 pages. But, in July of that year, a Linotype machine was installed in the offices of the New York Tribune and the age of mass-produced long length papers began. The New York Tribune is no longer in publication, but today The Times sells about 450,000 copies every day.

You must be logged in to post a comment.