Australian dressing station near Ypres 1917. The wounded soldier in the lower left of the photo has a dazed thousand-yard stare, a frequent symptom of “shell-shock”.

In wartime nations are often galvanised into frenzied action to innovate and invent in order to try to gain the upper hand in their struggle for survival. World War I was no exception. However as well as technical innovation the language and grammer of war changes also – new words and expressions are invented to describe and explain the changing face of war. In this article we look at some of the terms, still in use today, that owe their origins to this conflict.

WWI Speak

While the term camouflage first came to English in the late 1800s, back then it referred to general concealment. During the First World War, a new military-specific sense arose: “the act, means, or result of obscuring items or personnel to deceive an enemy.” Interestingly, the zoological sense of camouflage—the coloring or markings on animals that conceal them from predators or prey—also entered English during World War I.

A major topographical feature of the Great War was the intricate system of trenches that ran along the Western Front in Belgium and France. If soldiers were ordered to go over the top they were being told to climb over the parapet of a trench and charge against the enemy. The modern metaphorical extensions of over the top are not so deadly; rather, if something is over the top in a more general sense, it is extravagant or exaggerated.

In the case of the trench coat, form follows function. This rainy-season staple was first worn in the trenches of World War I. After the war, this practical military style became popular among civilians. A century later, trench coats can still be spotted under overcast skies.

Prior to World War I, plans were not described as hush-hush. This term meaning “highly secret or confidential” entered English in the 1910s and surged in usage during World War II, according to Google Ngram Viewer.

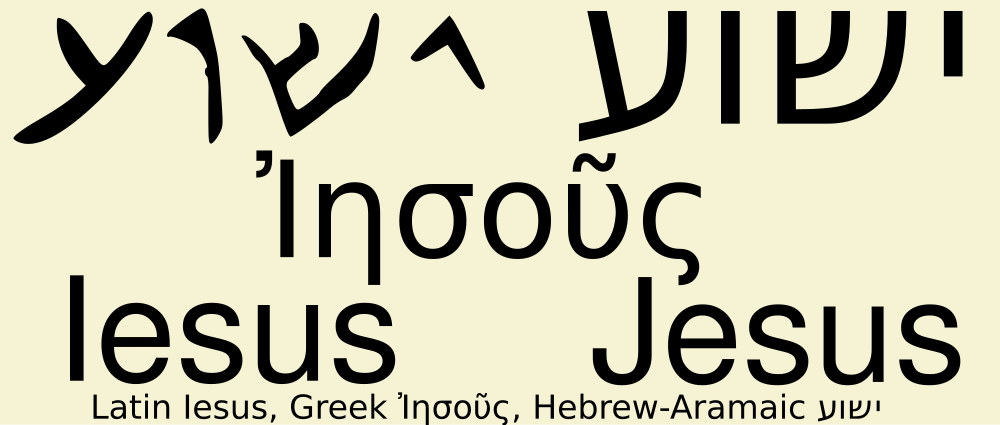

Shell shock first came to English in 1915 as soldiers began to exhibit signs of psychological damage from their time on the front. The term post-traumatic stress disorder didn’t enter English until the 1970s, though post-traumatic stress syndrome predates this by about 10 years.

The term cushy was widely used by military personnel in World War I to describe something involving little effort in return for ample reward. The term existed before the 1910s, but during the First World War cushy also began to be used to describe a wound that was serious enough to send you home, but not serious enough to kill you or to cause lasting damages. In the Britain, such a wound was called a blighty. This term derives from the Hindi word bilayati meaning “foreign,” and has been used by British soldiers in India to refer to England since around 1900. The 1916 song “Take Me Back to Dear Old Blighty” was a popular wartime tune.

The verb mock up first entered English during World War I to describe the making of a replica used for study, testing, or teaching. The Oxford English Dictionary’s first recorded evidence of this verb comes from Winston Churchill in 1914: “It is necessary to construct without delay a dummy fleet…They are then to be mocked up to represent particular battleships of the 1st and 2nd Battle Squadrons.” The noun mock-up dates from slightly later in 1920.

Next time you hear a child say that a classmate of hers has cooties, think of the Great War. Cooties came to mean “lice” during World War I, and since the 1950s has referred to the imaginary germs infecting children of the opposite sex. Etymologically unrelated to this sense is cootie in Scots meaning “a wooden bowl,” first recorded in the late 1700s.

You must be logged in to post a comment.