On August 16, 1858, the first ever message was sent across the Atlantic by telegraph cable it read : “Glory to God in the highest; on earth, peace and good will toward men”.

The transmission marked the culmination of 19 years of dreams, plans setbacks and hard work.

THE ELECTRIC TELEGRAPH

The idea of a transatlantic communications cable was first mooted in 1839, following the introduction of the working telegraph by Briton Wiliam Cooke and Charles Wheatstone. Soon after in 1840, Samuel Morse, the inventor of Morse code threw his backing behind the idea. Progress in the telegraph industry prgressed and by 1850 a link had been laid between Britain and France. That same year construction also began on a telegraph line in North America from Nova Scotia to the very tip of Newfoundland.

The team behind the east-coast cable was led by Frederick Newton Gisborne, a telegraph engineer from Lancashire living in Nova Scotia. It was at this time that Gisborne came up with the idea that the east-coast cable could be extended across the Atlantic to Britain. However in 1853 the company behind the new line in Nova Scotia collapsed.

However the idea was given a new lease of life when Gisborne was introduced to Cyrus West Field, a businessman and financier from New York City. Field took Gisborne’s idea and set about making it happen. He consulted Morse on the technical requirements, as well as the noted oceanographer named Matthew Maury. Satisfied that the project was feasible, he formed the “New York, Newfoundland and London Telegraph Company”.

BUILDING ON AN IDEA

Field began to raise funds for the transatlantic expedition by selling shares in London and in New York in a parent company called the Atlantic Telegraph Company. The British government helped Field out with a subsidy of £1,400 per year, which works out as about £150,000 today, and the financier managed to get the US congress to help out, too, despite fierce opposition from Anglophobe senators. Field also supplied a quarter of the funds for the cable himself.

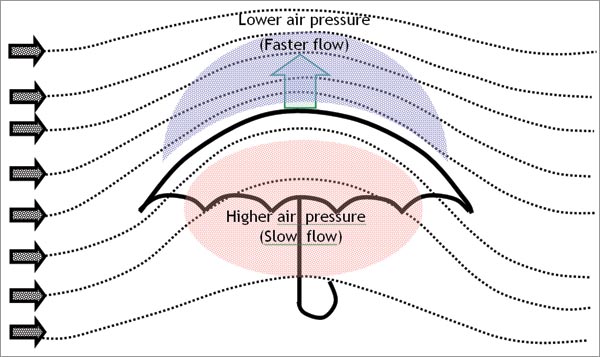

In 1857, the first attempt was made. A cable consisting of seven copper wires was manufactured by a pair of English companies — Glass Elliot & Co from Greenwich, and R.S.Newall & Co from Liverpool. The cable’s protective qualities were important — it was covered with a latex made from gutta-percha, which was thought to be resilient to attack from marine plants and animals, wound with tarred hemp and surrounded by a spiralling sheath of iron wire. The idea was to allow for a pull of several tons, but still be relatively flexible.

In 1857, the first attempt was made. A cable consisting of seven copper wires was manufactured by a pair of English companies — Glass Elliot & Co from Greenwich, and R.S.Newall & Co from Liverpool. The cable’s protective qualities were important — it was covered with a latex made from gutta-percha, which was thought to be resilient to attack from marine plants and animals, wound with tarred hemp and surrounded by a spiralling sheath of iron wire. The idea was to allow for a pull of several tons, but still be relatively flexible.

Two ships — the HMS Agamemnon and the USS Niagara — set sail from near Ballycarbery Castle in County Kerry, on the southwest coast of Ireland on August 5, 1857. On the first day of the expedition, however, the cable broke and had to be grappled from the sea floor and repaired. Soon after, the cable broke again at a depth of 3.2km, and the operation was called off for the year.

Undaunted, Field attempted the connection again the following year. After experiments in the Bay of Biscay had been conducted, the plan was changed — the Niagara and Agamemnon met in the centre of the Atlantic on 26 June and attached their respective cables to each other, then headed for opposite sides of the ocean. Again, the cable broke — once after less than 6km had been laid, again after about 100km and then a third time when 370km had been laid. The boats returned to port.

A THIRD ATTEMPT

Despite low morale among the crews, a third expedition set out. The boats met in the centre of the Atlantic on 29 July, 1858, and attached the cables together. The ships veered off-course wildly, due to the ships’ compasses being affected by the magnetic field generated by the electrically-charged coiled cable, but that problem was solved by a pilot boat used for navigation. Crucially, there were no cable breaks, and the Niagara made it to Trinity Bay in Newfoundland on 4 August, and the Agamemnon arrived at Valentia Island off the west coast of Ireland on 5 August. Over the following days, the shore ends were landed on both sides using a team of horses, and tests were conducted.

Then, on 16 August 1858, the first message was successfully sent, and was swiftly followed by a telegram of congratulation from Queen Victoria to US President James Buchanan, which expressed a hope that the communications cable would create: “an additional link between the nations whose friendship is founded on their common interest and reciprocal esteem”.

President Buchanan replied with a rather more flowery response saying : “it is a triumph more glorious, because far more useful to mankind, than was ever won by conqueror on the field of battle. May the Atlantic telegraph, under the blessing of heaven, prove to be a bond of perpetual peace and friendship between the kindred nations, and an instrument destined by Divine Providence to diffuse religion, civilization, liberty, and law throughout the world”.

His verbose message will have caused headaches for the operators. The reception across the cable was terrible, and it took an average of two minutes and five seconds to transmit a single character. The first message took 17 hours and 40 minutes to transmit.

TEETHING TROUBLES

On 3 September, 1858, the cable failed. In an attempt to increase the speed of transmission, the voltage on the line was boosted from 600V to 2,000V, and the insulation on the cable couldn’t cope. It failed over the course of a few hours, and it would be another six years before the capital was raised for another attempt.

THE LEGACY

However, although we’re now laying fibreoptic cables rather than copper ones, the techniques in laying and protecting the cables are still remarkable similar. The cable is still covered with helical steel wires to protect the central core, and breaks are found by testing the resistance of the metal inside to determine the length before there’s a break.

The major difference is the capacity. The first few cables could only manage a few words per minute but modern submarine cables can transmit more like 84,000,000,000 words per second.

A GREAT BRITISH INVENTION

A GREAT BRITISH INVENTION

You must be logged in to post a comment.