Introduction

Up until 2008 Sark was the last feudal territory in all of Europe. Not surprisingly Sark’s history is linked to the tenure of the different feudal families that either inherited or bought the rights to the fief.

Early History

Stone-age man was in Sark 3000-2000 BC. Sark along with the other Channel Islands were actually islands at this time the sea levels having risen after the last Ice-Age to cut them off from mainland Europe. However these early Sarkees only left a few minor megalithic structures; over centuries these have been eroded by the islanders in their search for suitable building stone, and little now remains. The Romans may briefly have maintained a garrison in Sark; they, or possibly some Gauls trying to escape from them, left a few artifacts and some coins, but no durable buildings. The existence of a Visigothic settlement, probably of the 5th century, has been deduced from the remains of a bronze foundry discovered in the 19th century.

The recorded history of Sark begins about AD 557, when the Channel Islands were incorporated into the Celtic Diocese of Dol in Brittany and were visited by the Bishop, St Sampson, by St Helier, and by St Magloire. St Magloire came again in AD 565 and established in Sark a community of some 60 Breton monks; they built a chapel and living quarters; they dammed a small stream to make fishponds and to drive a water-mill; and they enclosed some pasture land. This community continued in existence for some eight centuries.

The next certain date is 933, when the Channel Islands were granted by the French King in fief to William Long-sword (d. 943) who had succeeded his father Rollo, the first Duke of Normandy. About this time the Islands were transferred from the Diocese of Dol, in the Celtic Church, to that of Coutances in the Roman Church. St Magloire’s monastery in Sark then came under the Abbey of Mont St Michel, and it was rebuilt as a priory. In 1066 William the Conqueror added the Kingdom of England to his Duchy of Normandy; this made little difference to the islanders who continued to pay homage to him as Duke even after he became King of England. In 1199 “Richard the Lion Heart” was succeeded by his brother John as King of England and Duke of Normandy, but the French invaded Normandy and John lost his mainland Duchy.

Following this French invasion of Normandy the larger islands were heavily fortified, but Sark, being naturally almost impregnable, was given no more than a simple tower or keep; a length of very thick ancient wall at La Seigneurie is thought to be a fragment of such a fort. The lawlessness of the Hundred Years’ War continued into the 14th century and made life untenable for the monks in Sark, so that by the middle of the century they had all returned to France. Of the priory or monastery, dating from the 10th and later centuries, little now remains. The departure of the monks seems to have left the islanders without guidance or leadership, and in 1369 the French raided Sark so devastatingly that it remained virtually uninhabited. There is a well-entrenched legend that the Island then fell into the hands of pirates and wreckers, who with false lights would lure ships onto the rocks and plunder them. There is an interesting tale of how they were eventually driven out of the island, although its’ veracity is hard to confirm.

French Occupation

From the latter part of the 14th century, after the French raid, until the middle of the 16th century, over a span of nearly two hundred years, Sark appears to have been uninhabited, or at least uncivilised and without government. In 1549 a large French force landed and set up a garrison of some two hundred conscripts, convicts, or mercenaries, under Captain Francois Bruel. He built three forts: Le Grand Fort in the north of the Island to cover the landings at L’Eperquerie and La Banquette, Le Chateau de Quenevets on the headland above Dixcart Bay, and a third at Vermondaye in Little Sark.

The garrison was soon reduced, by desertions or escapes, to a mere handful, and in 1553 it was easily overcome by the Flemish adventurer Adrian Crole. He took some French prisoners and landed them in Guernsey; he then went on to London to report his deeds to the Ambassador of the Emperor Charles V, hoping for a handsome reward. The Emperor, it seems, was not interested and Crole was referred to Queen Mary Tudor; she ignored his request and he went back to Sark disappointed. He collected ‘ordnance’ and other valuables from the French forts and then returned to Holland, stopping on the way to sell some of his booty to the Captain of Alderney. The Governor of Jersey sent a party to demolish the French forts, and Sark was then again left untenanted.

In 1560, when the Island had been unoccupied for six or seven years, the Seigneur of Glatigny in Normandy obtained a lease from the King of France – who was hardly entitled to grant it – and set up a colony of tenants from his Normandy estates. In 1562, however, war again broke out between England and France; it may be supposed that Glatigny thought his tenure none too secure for he took his people back to Normandy. Sark was once again left uninhabited. The following year, 1563, may be said to mark the beginning of Sark’s modern history with the colonizing venture of Helier de Carteret under the patronage of Queen Elizabeth I.

The de Carteret family (1563-1720)

Helier de Carteret was the hereditary Seigneur of the Manor of St Ouen, the principal fief of Jersey. St Ouen is in the north-west corner of Jersey facing towards Sark; Helier, with Glatigny in mind, saw a threat of French encroachment in an unoccupied island, and he decided that Sark must be colonized. The Island was in the Bailiwick of Guernsey, and Helier therefore had to obtain the authority of the Governor of Guernsey, who acted for the Crown, to occupy Sark. With the help of a Guernsey friend, Nicholas Gosselin, Helier obtained the concession in 1563 and the following year took a party of his tenants from St Ouen to Sark. They made some trial grain sowings and, finding the land fertile, were encouraged to press on with the colonizing scheme.

A couple of years later, in 1565, Helier was in London on Jersey affairs; he took this opportunity to seek royal confirmation of his tenure of Sark. From Queen Elizabeth he obtained Letters Patent granting him the Island of Sark as an addition to his fief of St Ouen. For this he undertook to pay a small annual rent and to provide at any time forty men armed with muskets for the defence of the Island.

The settlers, led by Helier and his redoubtable wife Margaret, faced a forbidding task; the ruined chapel of St Magloire was patched up for the de Carteret household to live in; there were otherwise no houses, though the stones from the demolished French forts were quickly put to good use. There had been no orderly cultivation for nearly two hundred years, and the land was a wilderness of gorse and brambles, riddled with rabbits. All the settlers’ livestock, seed grain, tools, timber for building, and supplies for subsistence had to be shipped from Jersey and unloaded at one or another of Sark’s precarious landing places. Helier had proved at the beginning how fertile the land was; he believed that efforts to cultivate it would be rewarded and that the huge expense of the venture would be justified, as indeed it was. To ensure that he could at all times muster the forty men required in the Queen’s charter, Helier divided the Island into forty land-holdings, collectively known as La Quarantine, comprising his own manorial land and thirty-nine sub-fiefs or tenements leased to tenants under obligation of tithe and labour and the service, when required, of an armed man for the defence of the Island – who in practice would be the Sieur (tenant) himself or a member of his family. The system of land-tenure that evolved out of this arrangement became the basis of the Island’s constitution and government. Helier set up his own holding, Le Manoir,* in the centre of the Island near a spring at the head of the valley that goes down to Dixcart Bay. The thirty-nine tenements were arranged so that each included a stretch of the coast with possible landing places to be defended, as well as enough workable land to support a family, and some cotils or cliff-top grazing. Helier entrusted four tenements in the west of the Island to his friend Nicholas Gosselin of Guernsey, who had helped him to obtain the preliminary concession in 1563. These four tenements were held by Guernsey people brought by Nicholas, after whom Le Havre Gosselin is named.

Helier was again in London in 1572, when he gave the Queen an account of his achievements over the seven years of his tenure. She rewarded him by making Sark a Fief Haubert* and giving him six bronze cannons from the Tower of London, one of which, suitably inscribed, is preserved at La Seigneurie. Another of Helier’s undertakings, begun in 1570, was the building of Le Creux Harbour at Baie de la Motte, which he regarded as more accessible for boats from Jersey than the unprotected landings at L’Eperquerie and La Banquette in the north of the Island. Le Creux, however, was almost inaccessible from the land until Philippe de Carteret (Helier’s son and successor) cut the tunnel, dated 1588, and made the road up to La Collinette. Helier also built the windmill which stands in Rue du Moulin a short distance to the west of Le Manoir.

After some fifteen years as active Seigneur, Helier in 1579 conferred the governing of Sark on his son Philippe and retired to his St Ouen estate. Philippe achieved nothing very remarkable beyond improving the access to Le Creux Harbour. His attempt to make Sark an independent bailiwick, separate from Guernsey, was unsuccessful.

The Fief of Sark continued to be held, but was seldom visited, by successive generations of the de Carteret family. A difficult situation arose during the English Civil War; Jersey was Royalist, as also the de Carteret family and, by implication, most of the Sieurs of the Quarantaine in Sark. Guernsey, however, was Parliamentarian, and Sark was in its Bailiwick. Under the Commonwealth the royal fiefs were confiscated by Parliament, and the de Carterets could not go to Sark, which was governed from Guernsey; in particular the Guernsey family of Le Gros became de facto rulers of Sark. After the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660 the Seigneur, Sir Philippe de Carteret III, regained possession of his fiefs, and Sark’s former system of government was more or less restored. In 1693 the fief passed to Sir Charles de Carteret, then aged about 15; he managed Sark’s affairs no better than he did his own life, and he died childless and heavily in debt in 1715. He was the last of the de Carterets who had held the Fief of St Ouen in Jersey for seven centuries.

*A Fief Haubert, or Knight Service, is held direct from the Crown

The Fief of Sark, encumbered with debts, then passed to Lord John Carteret, a member of the anglicized branch of the family, who never went to the Channel Islands and was not interested in the affairs of Sark beyond eliminating the debts. In 1720 he sold the Fief, with Royal Assent, to Colonel John Johnson of Guernsey, who was the principal creditor; the Colonel died in 1723 and the Fief passed through several hands until it was bought in 1730 by Susanne Le Pelley, nee Le Cms, widow of Nicholas Le Pelley and tenant of La Perronerie, one of the forty holdings.

The Le Pelley tenure (1730-1852)

Susanne Le Pelley, of the Le Gros family, thus became in 1730 the first Dame of Sark; she founded a dynasty that continued until 1852 – for almost as long as the century- and-a-half of the de Carteret tenure. The Le Gros and the Le Pelley families were Guernsey people, and Sark thus became more closely attached to Guernsey, while the Jersey influence waned. Susanne, on becoming Dame, decided to remain in her family house at La Perronerie, rather than move to Le Manoir, which was the traditional residence of the Seigneur. She accordingly set up the Seigneurie at La Perronerie, and the house of Le Manoir became the residence of the Minister or Vicar, which it continued to be until 1934, when a new Vicarage was built. The house of La Perronerie, built about 1675 and much added-to over the years, succeeds an earlier building on or near the site of the Priory established by the Abbey of Mont St Michel in the late 10th or early 11th century. As mentioned earlier, the monks abandoned the Priory in the 14th century, and the buildings were dismantled by the islanders wanting stone for their houses. Susanne’s successors in the 18th century lived in Guernsey for most of the year and used their Sark estate as a summer resort. The Island became fashionable for week-end parties and wedding celebrations – said to have been riotous at times – engendering among the islanders no little resentment. This coincided, at the turn of the century, with anti-feudal and anti-aristocratic sentiments inspired by the French Revolution, and with the rise in England of Methodism and its stricter moral standards. The islanders readily welcomed a Methodist missionary from Guernsey, who in 1789 preached in the evenings in the kitchen at Clos a Jaon (at the corner of Chasse Marais and Rue du Sermon). The Methodist Ebenezer Chapel was built in 1796 – twenty-four years before the Anglican church of St Peter. The chapel was popularly known as Le Sermon, whence Rue du Sermon is named. Pierre Le Pelley II (great-grandson of Susanne) gave the land and arranged for the building of St Peter’s Church, to replace the ‘rotten old barn at Le Manoir that was still being used. St Peter’s was completed in 1820 and consecrated in 1829

The Silver Mines

A relic from the Sark Silver Mines

In the early 1830s traces of copper were found at Le Pot, but the fact was overshadowed by the discovery in 1835 of silver ore near-by at Port Gorey. A company was formed to exploit the lode; some two hundred Cornish miners were brought in, and four shafts were sunk to amazing depths as great as 180 metres, which is 120 metres below water level, with immense lateral galleries following the silver veins, some stretching out under the sea. A massive 120 horse-power steam pumping-engine was installed, with other machinery for treating the ores. The young Seigneur, Pierre Le Pelley III, was persuaded to invest in the mining venture; the company claimed to be finding ever-richer ores requiring ever-greater capital outlay, and prospects were made to look very promising. Pierre was drowned in a storm off the Bec du Nez* in 1839 and was succeeded as Seigneur by his younger brother Ernest, who inherited Pierre’s shareholding in the silver mine and even made a further investment in it. In 1845, when the company’s prospects had never seemed better, first a valuable cargo of silver ore was lost at sea, and soon afterwards the lower, richer, galleries were flooded and lost beyond hope of recovery. The value of the ore produced up to then was £4,000, from a Remains of the silver mines capital expenditure of £34,000. The company was wound up a few years later. Ernest Le Pelley was bankrupt; with Royal Assent he mortgaged the Fief to a rich Guernsey financier named Jean Allaire, whose fortune was reputedly derived from privateering during the Napoleonic Wars. When Ernest died in 1849 his son Peter Carey Le Pelley, aged 19, inherited the Fief and the debts; he was unable to meet the interest charges on the mortgage, and in 1852 he surrendered the Fief to Allaire’s daughter Marie, the widow of Thomas Guerin Collings. Marie thus became the second Dame of Sark, but she died in the following year and was succeeded by her son The Revd. William Thomas Collings. It was he who established the dynasty that continues today and has already exceeded the duration of the Le Pelley family.

The Collings-Beaumont family (1852-Today)

The Revd. William T Collings was perhaps the most dedicated Seigneur since Helier de Carteret; he loved Sark, lived here much of the time, and was interested in the Island’s affairs. He organized the rebuilding of Le Creux Harbour and he cut the second tunnel in 1866; he added the chancel to St Peter’s Church in 1878, and he gave a parcel of Seigneurie land for an extension of the cemetery. He also had the ancient prison removed from alongside the church in 1856 and rebuilt where it now stands at the western end of The Avenue; he bought the tenement of L’Ecluse, which adjoins La Perronerie; and he added the watch-tower to the Seigneurie house – considered by subsequent generations to be a rather regrettable lapse of taste.

The Revd. William was succeeded in 1882 by his son William Frederick, whose tenure of the Fief lasted for 45 years; during this time the tourist business became important; excursion steamers used to come from Jersey and Guernsey two or three times a week; the hotel trade flourished, and Sark began to be known in the world. William Frederick died in 1927 and was succeeded by his daughter Sibyl Mary, the widow of Mr Dudley Beaumont; she was thus the third Dame in Sark’s history, and she was by far the most notable. Two years after becoming Dame she married Mr Robert W. Hathaway, an American citizen naturalized British; he was thus legally Seigneur, but in practice he preferred to leave the government of the Island to his wife.

Sibyl Hathaway was the Dame of Sark who became a legend and is still justly renowned; she was a person of strong character who governed her Fief wisely and devotedly for 47 years, and lived to the age of 90. She was never more formidable than during the German occupation of Sark, 1940-45; she refused to leave the Island, and when the occupying German officers arrived she told them, in fluent German, what they were allowed and not allowed to do on her Island. They recognized authoriy when they met it, and they treated her with respect. The German occupation of the Channel Islands is a horrifying chapter in their history; Sark, it seems, suffered somewhat less than did the larger Islands, partly because of its very small population and its geographical unimportance, and partly – perhaps chiefly – because of the Dame’s authoritarian presence. When in 1957 Queen Elizabeth II, with Prince Philip, visited Sark she was the first Sovereign to do so (Queen Victoria had tried in 1859 but the sea was too heavy for her to land). On this occasion the Dame was able to render her homage to her Sovereign in the very terms in which Helier de Carteret had paid homage to Queen Elizabeth I. A few years later, when celebrating the 400th anniversary of the first charter, Sibyl Hathaway became, as she put it, a ‘double Dame’ when she was created Dame of the British Empire. Dame Sibyl died in 1974 and was succeeded by her grandson John Michael Beaumont. He has continued her policy of preserving traditions that serve a good purpose, or are at least harmless, while conceding change where advantages lie. The islanders’ views appear to run on the same lines.

Thus their long-established refusal to admit motor-cars to the Island was later endorsed and extended by their rejection of proposals for a helicopter service from Guernsey. On the other hand, the practical advantages of allowing tractors were presumably found to outweigh the disadvantages of the consequent pollution. Sark has so far managed to avoid becoming entirely part of the modern world, and it consequently has enormous but vulnerable charm. Nobody appreciates this more than the Seigneur and the islanders themselves.

Breqhou and the end of Fuedalism

The Fief conferred by Queen Elizabeth’s Charter of 1565 consisted of the Island of Sark and all adjacent islets and rocks.

Brecqhou, though part of the Fief, was not included in the original distribution of land among the thirty-nine Sieurs or tenant farmers by Helier de Carteret. It became a tenement in 1927 when Dame Sibyl sold its lease and transferred to it the vote pertaining to La Moinerie de Haut, a tenement that had become part of La Seigneurie.

In 1993 it was sold to the Barclay brothers, who objected to the treizieme that they were required to pay as a tax to the Seigneure along with the antiquated laws which required that land and property could only be willed to the eldest son. The dispute was protracted and ended up in the Europen courts of Justice and ushered in a painful process of change that has ultimately led to the end of Feudalsim and the introduction of full democray into Sark.

On 10 December 2008, the Island held its first democratic elections in which 28 Conseillers were elected to Chief Pleas by universal adult suffrage and secret ballot.

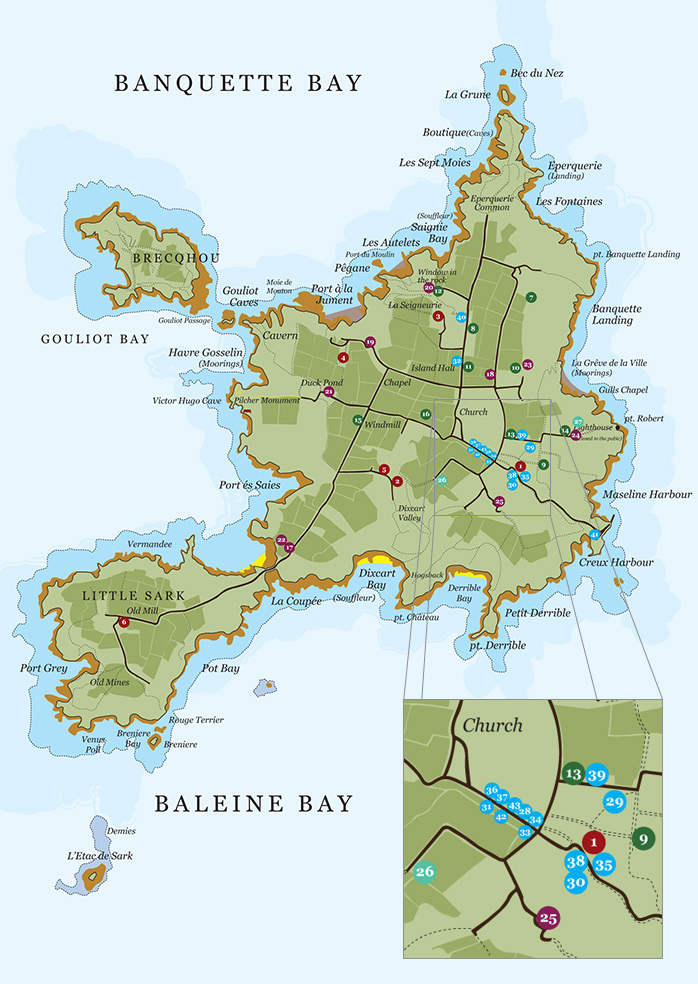

Modern Day Sark Map

Hotels

1 Aval du Creux Hotel

2 Dixcart Bay Hotel

3 La Moinerie Hotel

4 Hotel Petit Champ

5 Stocks Hotel, Tap Room and Stable

6 La Sablonnerie Hotel

Guest Houses

7 Beau Pre

8 Beau Sejour Guest House

9 La Chaumiere

10 Clos de Menage Country House

11 Clos Princess

12 La Maison Rouge & Gallery

13 La Marguerite

14 Notre Desire

15 Sue’s B & B and Tea Garden

16 Le Vieux Clos

Self Catering

17 La Carriere

18 Cartref

19 Dower Cottage

20 L’ Ecluse

21 Petit Beauregard

22 Port es Saies

23 Stable Cottage

24 La Valette

25 Le Vallon d’Or

Campsites

26 Pomme de Chien

27 La Valette Campsite

Businesses

28 Avenue Cycle Hire

29 A to B Cycle Hire

30 Sark Carriage & Cycle Hire

31 Foodstop

32 Island Hall

33 La Petite Poule

34 Sark Estate Agents

35 Bel Air Inn

36 Time and Tide

37 Coastline & Sea Horse Studios

38 The Red Room

39 Aladdin’s Cave

40 La Seigneurie Gardens Trust

41 Jimmy’s Carting

42 Sark Glass Take 2

43 Naturally Sark

You must be logged in to post a comment.