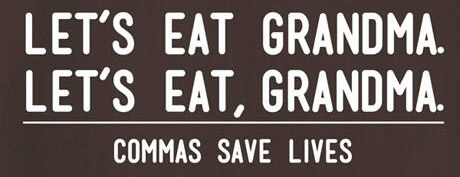

As this rather humorous illustration shows, punctuation really does add more meaning to the written word than we often give these little characters credit for.

So When Was Punctuation First Used In Any Language ?

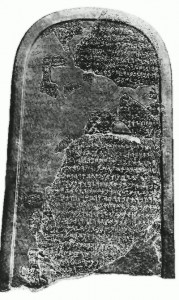

It is thought that the world’s first punctuation marks appeared on the Moabite Stone, AKA the Mesha Stele. This inscribed stone dates from around 840 BC and tells of the greatness of King Mesha of Moab (in modern-day Jordan); it features points between words and vertical strokes to mark the end of sections that might be comparable to biblical verses.

Most historians believe that punctuation as we know it today was invented to show how a text should be read aloud. By the 5th century BC, Greek playwrights were using some basic symbols to show where actors should pause, and the scholar Aristophanes of Byzantium (c257-cl85 BC) invented a formal system of punctuation. He also designed accents to aid pronunciation.

Most other ancient written languages in their original forms-Sanskrit, Arabic, Korean, Chinese, Japanese, etc – used little or no punctuation, though some Chinese scrolls from around 400-300 BC sometimes used symbols to denote chapter and sentence endings.

Punctuation in its modern form owes a lot to the Renaissance and, particularly, the Italian scholar and printer Aldus Manutius (1449-1515), but also to the Reformation and the printing of Bibles in local languages. These were, of course, intended to be read aloud. Our modern system of punctuation didn’t emerge till the 19th century.

English/American punctuation is now used more or less wholesale across Europe and many aspects of it have been adapted in most other parts of the world.

What Do Those Little Marks Mean In English …

COLON ( : )

Not to be confused with the end of the large intestine, grammatically, the colon marks a major division in a sentence. The sign may also precede lists or summations or even help to categorize numbers, like separating hours from minutes as in “5:30.” The word comes from the Greek kolon meaning “limb” or a “part of verse.”

SEMI-COLON ( ; )

This punctuation mark, called “dangerously addictive” by Virginia Woolf, unites two independent clauses with a common thematic tie: “Leonard had nothing against tigers; he grew up with cats.” In this example the two clauses would be perfectly permissible sentences on their own, but because they both relate to the same person and the same affection for felines, they are appropriately linked with a semi-colon. The addition of the prefix semi-, meaning “part,” to the Greek root kolon meaning “part of verse” makes the semi-colon quite literally a part of a part.

COMMA ( , )

Aside from the period, the comma is the most common punctuation mark in English. The word is derived from the Greek koptein meaning “to cut off,” fitting for our beloved comma’s use in marking pauses within sentences and separating terms in a list. The mark was invented by the Italian printer Aldus Manutius in the late 1400s, a time when the slash mark signified a pause. Manutius lowered the slash mark in relation to the line of text and curved it slightly around the final letter. This freed the slash mark to indicate a comparison and simultaneously gave birth to the comma.

ELIPSES ( … )

“I think I love you…” If you’ve ever been confronted with this maddeningly indeterminate end to a sentence, then you’re no stranger to the effects of the ellipsis. From the Greek word elleipsein meaning “to fall short,” this punctuation mark indicates an omission or suppression of letters or words. Oftentimes readers can infer which terms are replaced by the ellipsis, but in certain settings there’s just no way to know.

APOSTROPHE ( ‘ )

In English, the apostrophe is the agent of contraction and possession, shortening words by replacing letters as in: can’t for “can(no)t,” and designating ownership as in: “the iguana is Lisa’s.” The word came to English in the late 1500s as a direct loan from the Middle French apostrophe meaning “aversion” or “turning away.” Following its induction into English, the symbol enjoyed extreme popularity in written text, the result of a centuries-long trend to imitate French culture.

QUOTATION MARKS ( ” )

Also called “inverted commas,” quotation marks set off dialogue, quoted material, titles of short works, and definitions by demarcating of a section of text: “Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore,” said Dorothy, as she opened the door. Before mechanized printing, quotations were indicated by identifying the speaker or using a different typeface, like italics. At the time single quotation marks indicated a pithy comment or quip. But by the 1740s, mechanical printing had taken off and printers adopted quotation marks to indicate speech.

HYPHEN ( – )

The hyphen is a short line used to connect the parts of a compound word. It may also be used to indicate a connection between the parts of a word that has been divided for other reasons like a line break. The term is derived from the Ancient Greek hypo + hen literally translated as “under one.” Historically, the mark was used to unite words or syllables, most likely indicating the way phrases were meant to be sung by Greek and Roman bards. Hyphens are still used today in choral notation to indicate connected syllables.

QUESTION MARK ( ? )

Also called the “interrogation mark,” the question mark is, in English, the punctuation mark placed after a sentence to indicate a question. In Spanish an inverted question mark is placed at the beginning of an inquisitive sentence as well. There is much speculation as to the origin of the question mark, but most attribute its invention to Alcuin of York, leading scholar and teacher in the court of Charlemagne. In the 8th century, Alcuin indicated questions in his writing with a mark like “a lightning flash, striking from left to right,” according to language writer Lynne Truss.

EXCLAMATION MARK ( ! )

This forceful punctuation mark indicates a moment of high volume or excitement at the end of a sentence. Though there is no consensus as to the origin of the exclamation point, many believe that it is an abbreviated composite of the Latin word for “joy,” io. After centuries of hurried handwriting, the “i” became a line, placed over the “o,” written quickly as a dot. The exclamation point was introduced into English in the 15th century as a “note of admiration.”

INTERROBANG ?!

This hybrid punctuation mark is the only symbol here that was born in the USA. The interrobang combines a question mark and an exclamation point to indicate a mixture of query and interjection or shock, as in: “She said what!?” In the case of the interrobang, both word and symbol are portmanteaus in that the word bang was used for “exclamation point” in 1950s secretarial vernacular. Similarly, the question mark is also known as the “interrogation mark.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.