Having a bath has uses aside from getting clean and reading a good book: it gives you an excuse to observe a bodily quirk that it would appear has been with us since Homo sapiens left the trees. Finger and toe-wrinkling takes about five minutes of full immersion for the effect to begin, but if you want maximum, scientifically proven wrinkles, then soak in salty water at 40°C (104°F) for 30 minutes.

Having a bath has uses aside from getting clean and reading a good book: it gives you an excuse to observe a bodily quirk that it would appear has been with us since Homo sapiens left the trees. Finger and toe-wrinkling takes about five minutes of full immersion for the effect to begin, but if you want maximum, scientifically proven wrinkles, then soak in salty water at 40°C (104°F) for 30 minutes.

Wrinkly Tales

The explanation for wrinkles is somewhat surprising, rather useful, and may tell us something about our pre-human ancestry.

In 1936, two researchers at St Mary’s Hospital in London were studying patients with paralysis in their arms. Thomas Lewis and George Pickering knew that the paralysis was caused by damage to the main nerve that runs down the arm all the way to the fingertips. What came as a surprise was that the fingers of their patients did not wrinkle when soaked in water. The patients’ non-paralysed hands and their feet showed normal wrinkling, but the wrinkles were absent from the paralysed hand. Nobody took much notice at the time and the story went quiet until 1973, when an Irish plastic surgeon, Seamus O’Riain, noticed essentially the same thing – or, at least, the mother of one of his child patients noticed smooth fingers where once there had been wrinkles.

It turns out that your fingers wrinkle because your body tells them to wrinkle. it’s not a passive effect, but an active decision that your body takes. We aren’t conscious of making that decision because it’s controlled by the automatic part of your nervous system that controls your breathing, heart rate and sweating. This can lead to some weird effects. For example, people who have severed fingers stitched back lose the wrinkles from the reattached fingers, until the nerves regrow and feeling and wrinkling return. You can also mess around with this by using drugs that shut down parts of the nervous system; they also turn off finger-wrinkling.

The evidence is conclusive: finger-wrinkling is nothing to do with water soaking into the skin and everything to do with an active control, albeit one of which we are not conscious.

How, then, does our body turn on and off fingerwrinkling?

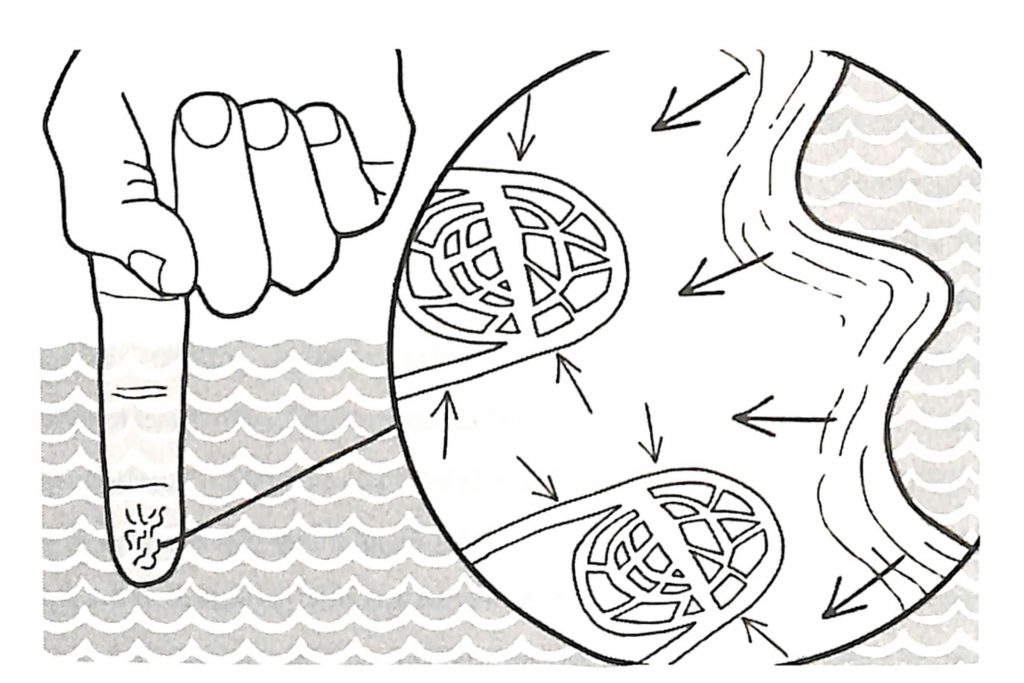

This is where the science becomes a bit more fuzzy and uncertain. Your fingertips do have sweat glands, despite what the commonly believed theory states. When sitting in a bath, water runs up these sweat glands and somehow signals to the body that we are soaking in water, which is why wrinkling takes a little while to get going. How this sets off the wrinkle signal is not known. One suggestion is that the water dilutes the sweat in the sweat gland and this change triggers the nearby nerves. What happens next has been carefully examined. The automatic part of our nervous system is very good at controlling how much blood flows to various parts of the body. In the case of wrinkling, the nerves tell the blood vessels to shrink, lowering blood flow especially to strange little balls of blood vessels in your toes and fingertips called glomus bodies. These are normally used to help reduce heat loss and keep your hands and toes warm. When the glomus blood vessels constrict, the whole glomus gets smaller, and the flesh under your skin shrinks a little. The skin on top, the stratum corneum, stays the same size, but since the flesh has shrunk underneath, the skin has to pucker up to accommodate this underlying change. So, it has nothing to do with water soaking into the skin, just that the flesh under your skin gets smaller and the skin on top stays the same.

Putting Wrinkling to Good Use

As with any good bit of science, this turns out to be a rather useful observation. it was Seamus O’Riain who first suggested using finger-wrinkling as a test of the health of the nervous system. There is now a standard protocol for soaking a patient’s hand and checking how finger wrinkles develop over time. lt is not a universally used test as it has a few problems. Firstly, when is a wrinkled finger wrinkled? How do you measure finger-wrinkling in an objective way? In addition, smoking and several routine drugs can inhibit your ability to wrinkle. These issues aside, being able to test a patient’s nerve health by just popping their hand in a bowl of water is jolly handy, if you will pardon the pun.

But Why Wrinkle Anyway?

So, that settles the big why do your fingers wrinkle debate, but it leaves one even more interesting question. Why does our body go to this effort on our behalf? Why would we have developed this strange ability to make wrinkles on our fingertips’ We don’t really know the answer to this yet; the only theory at the moment is that it gives us better grip.

But this does not answer my question of why our bodies should go to all this effort. This is where we can dive into the woolly depths of informed guesswork. Possibly, our ancient, pre-human primate ancestors might have evolved this trait to help them cope better in wet conditions. Imagine the daily torrential downpour in a rainforest: the branches of trees become suddenly slippery and slick with wet moss and lichens, our primate ancestors turn on their special wet-weather grip and hang on more effectively. Finger-wrinkling seems to be a quirk of our deep evolutionary past made present for us whenever we take a bath. The real explanation of how and why may not be the simple, elegant theory that you read so often, but it is a far more exciting and interesting one. That said, a 2013 study failed to find an improvement in grip in the wet, so the case is far from closed.