a word derived from the name of a real, fictional or mythical character or person after whom a discovery, invention, place, etc., is named or thought to be named.

Eponyms are one of the most fascinating examples of how the English language gains new words. In this article we take a colourful look at the phenomenon that is the eponym gathering together the stories of the people behind the words that have passed into our everyday vocabulary.

CHAUVINIST

How does an excessively misogynist person carry the name of Nicolas Chauvin, a simple French soldier in the Napoleonic wars who may or may not have existed?

‘Chauvinist’, both as a noun and adjective, and the condition of chauvinism, are nowadays almost exclusively used in the context of gender differentiation – male chauvinist pigs, usually.

Yet chauvinist originally meant excessively patriotic, and takes its root from Nicolas Chauvin, who was supposedly a foot soldier in the Army of Napoleon Bonaparte and who was distinguished by his blind patriotism, belief in French superiority and devotion to the Empereur’. He was allegedly badly wounded, even maimed, and may also have been honoured by Bonaparte himself.

The trouble with this eponym is that Chauvin may have been a fantasy as no one has ever found an official army or government record of such a person. His supposed character was used by many writers, however, usually as a figure of fun in the post-Bonaparte era.

In time, Chauvin’s excess of love for his country came to be analogously applied to over-the-top zealotry and claims of superiority of any kind. So next time someone calls you a chauvinist, male or female, do not return the insult but content yourself with the realisation that your knowledge, at least, is superior because you now know they are calling you after a man who probably didn’t exist.

DRACONIAN

Athens between 2,300 and 2,700 years ago was at the heart of Greek cultural development, which in turn influenced so many contemporary and later cultures, including those of Egypt and, above all, Rome. Socrates, Plato and Aristotle alone would have guaranteed Athens its place in history, but add the magnificence of the Acropolis inspired by the genius of Pericles, both a great general and art lover, and so many more writers, artists and philosophers, and you understand why classical Athens was and is so influential.

Yet it was not all sweetness and light in Athens. The city was ruled by powerful families with a system of blood feuds and unwritten laws until a much-maligned yet inspirational figure emerged towards the end of the 7th century BC.

Dracon, or Draco of Athens, basically invented zero tolerance to deal with lawlessness in the city. We know very little about the man himself, but he was clearly in a position of power around 620BC when he wrote the first constitution of Athens.

Solon, one of the original Seven sages of the ancient world, and the reformer that revamped Draconian law

The laws he laid down were extremely tough, so much so that they were reputed to be written in blood. Death was the punishment for just about every misdemeanour, even that of getting into excessive debt. On the other hand, Dracon was the first lawmaker to differentiate between murder and involuntary killing, a fairer law which underpins the western approach to capital crime to this day.

There is no doubt that, in a few short years, Dracon’s laws transformed Athens into a peaceable place.

The people of Athens allegedly showed their gratitude to Dracon in a bizarre fashion – in the custom of the time, one night in the theatre they honoured him by showering cloaks, capes, hats and other clothing upon him, which promptly buried poor Dracon and smothered him to death.

His name lives on as a byword for harshness, however, and, when JK Rowling was looking for a name for the ‘baddie’ in her Harry Potter series, she conjured up ‘Draco’ Malfoy.

HOOLIGANISM

Another highly disputed eponym, about which even the most scholarly of dictionaries disagree is ‘Hooligan’. The word certainly derives from the not uncommon Irish surname O’Houlihan or Houlihan. But whether that transformed into hooligan by way of a music hall song, or the activities of a rowdy family in Ireland in the 19th century, or through an infamous streetfighter in London in the late Victorian era is something of a moot point.

Recent research indicates that the first use of the word was in newspaper accounts of trials in 1890 involving young criminals in the south Lambeth area of London. They were described in press accounts of trials as ‘The Hooligan Boys‘, as they had Irish leaders, at least one of whom was a Houlihan. The Irish form of that name, which is presumably what was on the charge sheets, is written as ‘O hUallachain‘ – you can see for yourself that it might well be written or said in English as ‘hooligan’. The eponym caught on. Sadly, so did hooliganism.

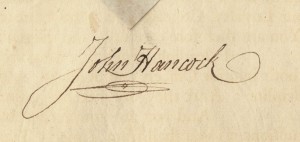

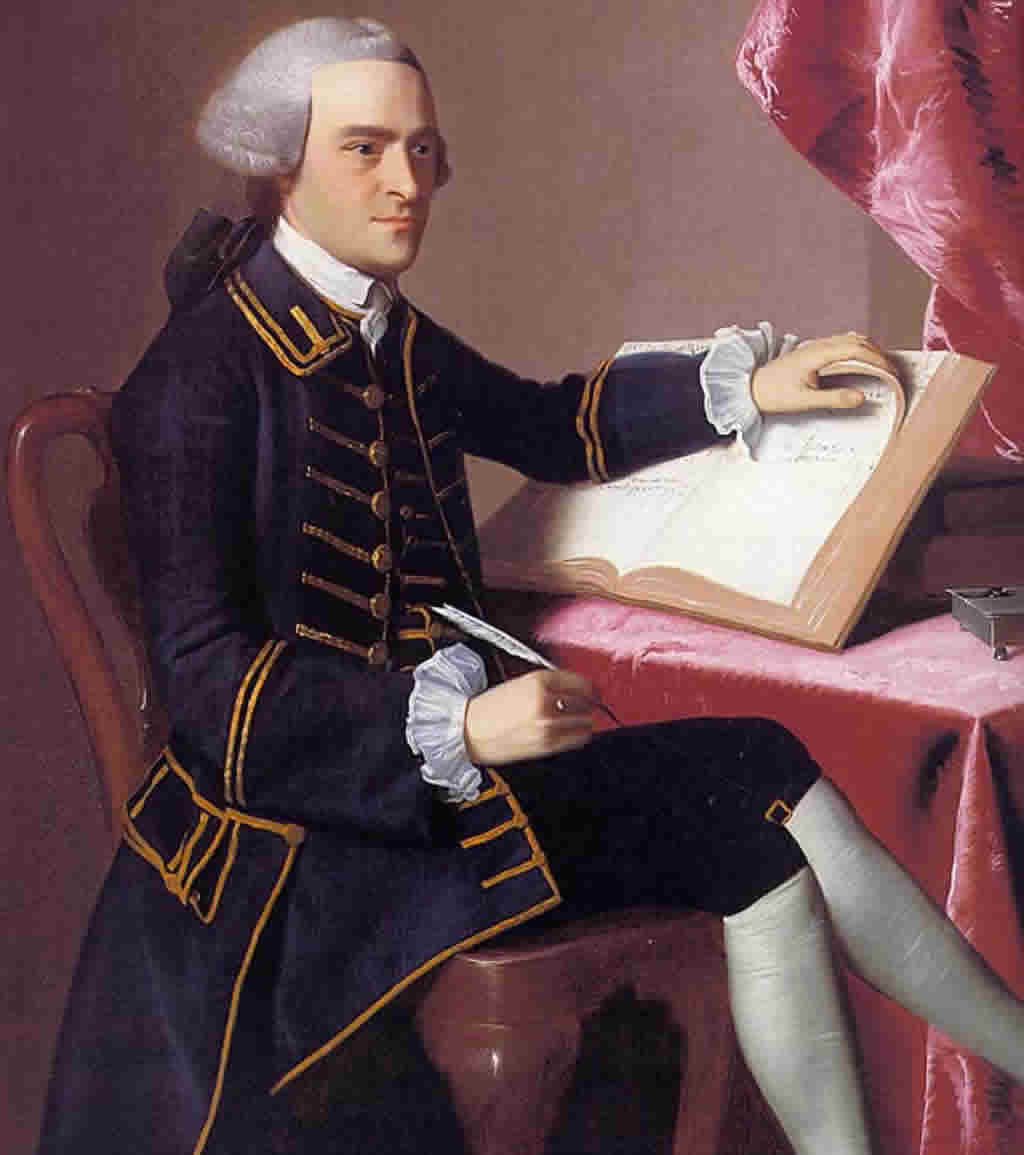

JOHN HANCOCK

This eponym is more used in America than here in Britain.

When he came to sign the Declaration of Independence, John Hancock (1736-93) did not mess about. A rich and hugely influential merchant from Massachusetts – it was said he financed the American Revolution – the British accused him of smuggling, but the charges did not stick. He became the President of the Continental Congress which declared independence in 1776. His bold signature is still seen as the most florid on the document and, in time, Americans came-to call any signature a ‘]ohn Hancock‘, proving that, like their British cousins, they will create an eponym out of respect.

When he came to sign the Declaration of Independence, John Hancock (1736-93) did not mess about. A rich and hugely influential merchant from Massachusetts – it was said he financed the American Revolution – the British accused him of smuggling, but the charges did not stick. He became the President of the Continental Congress which declared independence in 1776. His bold signature is still seen as the most florid on the document and, in time, Americans came-to call any signature a ‘]ohn Hancock‘, proving that, like their British cousins, they will create an eponym out of respect.

MENTOR

This word signifying a teacher-figure or adviser derives from the Greek mythological figure of Mentor, the friend of Odysseus who takes charge of his son Telemachus when Odysseus goes off to fight in the Trojan War and then gets lost for a decade.

You must be logged in to post a comment.