Rome’s invasion of Britain in 43AD would change the native Britons lives and culture forever. But this wasn’t the first Roman invasion. There was another nearly 100 years earlier by Julius Caesar. However he might have said “Veni, vidi, vici” * with regard to his Gallic wars across the Channel but it was very much a case of “Veni, vidi, reliqui” or “I came, I saw, I left” when it came to his invasion of Britain. We look at both in this article and what we know about the invasion and how the native Britons reacted to the Romans. * “Veni, vidi, vici” – “I came, I saw, I conquered.” : reportedly written by Julius Caesar in 47 BC as a comment on his short war with Pharnaces II of Pontus in the city of Zela (in Turkey). NOT in the Gallic wars … I’ve purloined it here for the invasion of Britain.

Why Did Caesar Only Come, Look and Leave Again ?

Rome first invaded Britain back in 55 BC. Julius Caesar had just spent 3 years conquering Gaul, but he knew that Britons were supporting the Gallic resistance there. So punitive attack to put the interfering Britons in their place was due. He intended not only to prove Rome’s might, but to return laden with booty and with military and political glory for himself – for the invasion and the conquest of a new, untamed land was an accepted traditional route to political success.

So he led 2 legions across the channel and arrived on the south coast of Britain in August 55 BC. However, the tidal waters at Deal made it impossible to beach his ships and his army was forced to wade ashore in full armour, leaving them in no state to meet the local warriors who were waiting for them. The Romans survived but victory eluded both sides because the Britons used guerrilla tactics and avoided a pitched battle of the kind that the Roman army was accustomed to.

When the weather worsened and the Roman fleet was virtually destroyed in a storm, Caesar retreated and limped home, having underestimated the resistance he would meet. He returned the following year, 54 BC, for a face-saving expedition, this time with more soldiers and the addition of cavalry to counter the Britons’ devastating, whirling war chariots. Shocked, the Britons buried their differences and united together under Cassivellaunus, the king of the Catuvellauni tribe. Tribal enmities proved too ingrained though and Cassivellaunus was betrayed: Caesar extracted tribute and eventually returned triumphant to Rome, but he never came back to Britain.

What Led Claudius to Invade ?

It was nearly 100 years before Rome invaded Britain again. After Caesar’s expedition, the geographer Strabo had written, rather defensively perhaps, that “although the Romans could have held Britain, they scorned to do so, because they saw that there was nothing at all to fear from the Britons (for they are not strong enough to cross over and attack us), and”, he continued, “they saw that there was no corresponding advantage to be gained by seizing and holding their country”.

Nonetheless, the limping, trembling and militarily inexperienced Emperor Claudius knew (like Caesar) that he needed military success to thrive in power, and that a prestigious invasion could provide him with the greatest honour any Roman could hope for: a triumphal procession in Rome and all the glory and popularity that went with it.

A victorious invasion of a barbarian land would also serve to boost Roman morale and to distract from troubles at home.

He was well equipped. Three years earlier, They were idle and dangerously restless, so, when a request for help came from Verica of the Atrebates tribe (who had been ousted from power by Caratacus, king of the Catuvellauni tribe), Claudius was ready.

How Did the Invasion Commence in AD 43 ?

The emperor gave command of the invasion to the general Aulus Plautius, who led legions, cavalry and auxiliary troops across to Britain. They arrived unopposed in three groups – though it is not clear where they landed: Richborough and the Solent have been suggested – defeated Catuvellaunian attacks and reached a river, perhaps the Medway or the Thames.

The Britons were carelessly encamped on the west side, thinking the Roman army couldn’t cross the fast, wide river without a bridge, but the Romans had recruited Celts who were practiced at swimming in full armour. These auxiliary troops crossed to the enemy camp and maimed the horses that drew the formidable battle chariots. The Roman advance towards London continued and the Catuvellaunian king Caratacus fled to Wales (where he instigated opposition to Rome for years).

No other tribe could come close to the military strength of the Catuvellauni and, one by one, they surrendered to Rome. Aulus Plautius now sent a message to Claudius, inviting him to come to Britain and to personally make a triumphal entry into Colchester. Some weeks later, Claudius arrived, together with war elephants. This wasn’t just for show, for their smell was known to drive enemy horses mad and the Britons’ skill in chariots was likely to be a real threat, even now. Colchester was taken, and Claudius declared Britain conquered. After just 16 days, he headed home to receive the applause and glory of a triumphal entry into Rome. Plautius was left to consolidate the conquest across the rest of Britain.

How Strong was the Roman Army ?

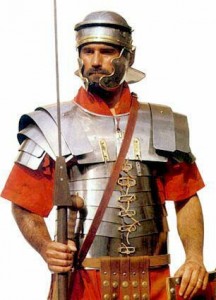

Aulus Plautlus commanded perhaps up to 40,000 professional soldiers in Britain. This army’s true strength, though, lay not just in numbers or in the mix of regular legionaries and skilled auxiliaries but in the way the soldiers trained together, spent their adult lives in military service together and,following precise orders, fought in a disciplined and controlled manner. The Britons, on the other hand, were fierce warriors who fought for individual honour, as and when required.

The contrasts were highly visual too: the Romans were heavily armoured (one legionary alone probably wore more iron in his helmet, breastplate and weaponry than most Britons saw in their lifetime) and they advanced as a unified whole, shields protecting neighbours, and with short, stabbing swords that encouraged close teamwork and close combat.

The Britons however – so the Romans tell us – looked more like beasts than men: ‘they howled battle shrieks and cries and fearlessly stripped off for battle, painted themselves with the blue dye of the woad plant, and caked their long wild hair and tousled beards and moustaches with limed water into white spikes. They excelled at ambushes and quick strikes, and fought so skilfully that they could launch spears and wield shields and swords at full gallop, leap on and off the chariots at speed, and even in mid-battle stand on the pole and run up and down from the chariot to the rugged but agile ponies.

The Romans’ speed was more measured: despite the weight of equipment they carried, they were hardened to long and swift marches, after which they would dig ramparts and set up marching camps each night. They would build strategic wooden (and later stone) forts for a more permanent presence – theirs was no hit and run invasion. The message was clear – they were here to stay.

Did the Britons Know the Romans were Coming ?

The arrival of the Romans was not a surprise to the Britons. Previous contact between them certainly existed: trade had, for decades, brought cultural influences such as coins and amphorae of wine to Britain; some Britons had fought with the Gauls against Rome in Caesar’s Gallic War – the military might and ambitions of Rome were not just recognised but had been experienced; and Caesar tell us some tribes, learning of the invasion from traders, sent envoys to him in Gaul to sue for peace. Nonetheless, the channel must have provided a buffer, a sense of protection, not just for the Romans, but for the Britons too who were engrossed in their own local tribal disputes. The first Romans may have seemed like just another border challenge.

After Caesar’s failed incursions, the Britons may even have felt rather superior. It was only the arrival of around 40,000 soldiers in AD 43 that prompted them to work together: either they were shocked into it (and therefore not so prepared after all), or perhaps they had already considered and prepared for the undignified possibility of having to forces against the common enemy.

You must be logged in to post a comment.