THE GUERNSEYMAN’s LIVELIHOOD

For nearly 150 years making a living, quite a good living actually, in Guernsey took a pecular turn. It was possible to become very rich via the dubiously ‘legal’ practices of Privateering and the less than legal smuggling trade. The Channel Islands became a centre of excellence in fighting the French, the Americans, ship building and ‘free trade’. Ancialliary industies supporting all this grew and floursished enriching islanders even further.

Some would say that little has changed and today’s finance industry is merely an extension of these industries … no comment.

PRIVATEERING

The age of Guernsey privateering began with the surrender of the privilege of neutrality in 1689 and lasted until Waterloo in 1815.

A privateer was defined as a vessel of war owned and equipped by private persons to seize and plunder enemy shipping. The master had to hold a licence from the Government called a Letter of Marque which was issued to a subject who complained of injustice done to him by a foreigner. These Letters allowed the commander of a merchant ship to seize enemy shipping either at sea or in harbour and to take them and their contents as prizes under the pretence of retaliation.

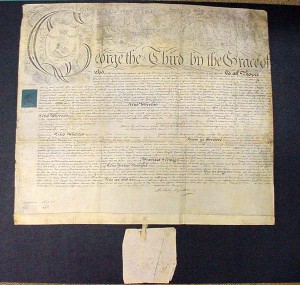

The Letter of Marque

The actual Letter of Marque was a very ornate, lengthy document on large sheets of parchment which carried the Sovereign’s portrait and Royal Arms at the head. Attached to the Letter was a wax impression of the Great Seal of the High Court of Admiralty.

The actual Letter of Marque was a very ornate, lengthy document on large sheets of parchment which carried the Sovereign’s portrait and Royal Arms at the head. Attached to the Letter was a wax impression of the Great Seal of the High Court of Admiralty.

The terms of sailing as a Privateer were very exact and the captain and crew were bound to a specific code of conduct, so that they were not considered to be mere pirates. There was a set rule on the distribution of prize money realised after each successful cruise. One fifth went to the King, two thirds of the remainder went to the owners, whilst the other third was divided between the captain, officers and crew.

There were also special awards of 4 guineas made to those men who first sighted the enemy ship or who were the first to board it. The Letter of Marque was given to the captain of the ship and not to the owners who sponsored it.

A Legitimate Career?

Privateering was a perfectly legitimate and, for some, a very rewarding enterprise until it was abolished by international agreement in 1856. So profitable was it to Guernsey for some 150 years that it could be called an Island industry because of the large numbers either directly or indirectly involved.

One of the most famous privateering captains was John Tupper who was eventually awarded a special medal in 1694 to reward him for his good services in destroying some French privateers.

For the next hundred years Guernsey privateers did extremely well financially, especially during the Seven Years War (1755-63) when their number greatly increased and took full advantage of the war between England and France. In 1800 it was estimated that the Island gained £1m through the capture of French and American shipping. In that year 35 more ships were fitted out in the Island and added to the Guernsey fleet, carrying 250 guns and 1,716 men.

Many of these ships were sponsored principally by the families of Dobrée, Priaulx, Le Mesurier and Le Cocq. Their prizes amounted to a further £1m between them.

An Extension to the Navy

The assistance rendered to the Royal Navy in times of war by the Guernsey Privateers was considerable. The Governor of Cherbourg wrote to Paris that

both Guernsey and Jersey were the despair of the French at the outbreak of each war.

Such was the help to the English and so great in number was the combined fleet of privateers that Westminster declared that the Islands were almost entitled to be called :

‘one of the naval powers of the world’

Many of the vessels were built and fitted out in Guernsey and gave rise to an expanding industry with, in 1834, no less than 8 boat builders and 5 ship builders in the Island.

The main yards were at Havelet, St Julian’s Rock, La Piette, Les Banques and St Sampson and provided work for such ancillary trades as sailmakers, sawyers and ropemakers.

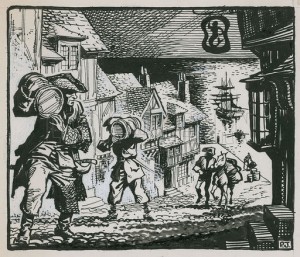

SMUGGLING

Guernsey indirectly owed to the privateers the introduction of what was, for some 50 years from the late 18th century, one of the Island’s leading industries, that of smuggling or ‘free trade’ as Islanders preferred to call

it.

Guernsey indirectly owed to the privateers the introduction of what was, for some 50 years from the late 18th century, one of the Island’s leading industries, that of smuggling or ‘free trade’ as Islanders preferred to call

it.

Wine and brandy stored in vaults in the Town matured very well in Guernsey’s mild climate and, together with her strategic position between France and England, combined to produce one of the chief entrepôts of smuggling.

The British Government regarded smuggling as illicit trading and tried to set up a Custom House in St Peter Port in 1707. This was strongly resisted by the Islanders, especially by William Le Marchant, then a Jurat and later to become Bailiff.

Another attempt at setting up a Custom House succeeded briefly around 1805, but the Lieutenant Governor had to issue a proclamation offering a reward of 50 guineas for information leading to the apprehension of ‘some evil-minded person’ who ‘had bored several holes in the bottom of one of the boats belonging to His Majesty’s Revenue’.