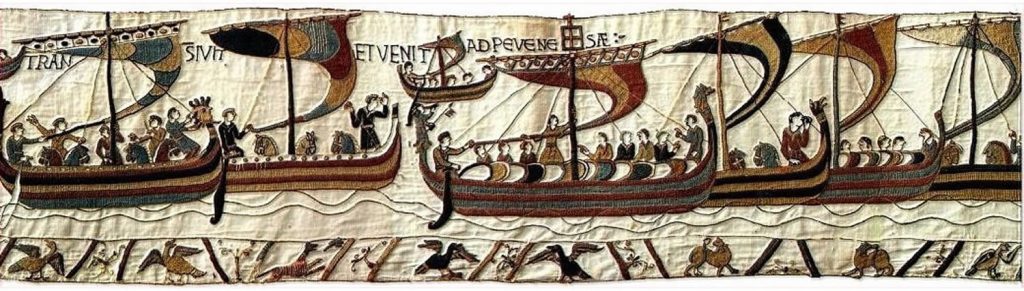

The Bayeux Tapestry tells one of the most famous stories in British history – that of the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. The vivid scenes on the Tapestry depict the events leading up to and including the Battle of Hastings and is one of Europe’s greatest treasures.

The story of the long life of the tapestry, incidentally its not technically a tapestry but an embroidery, is every bit as exciting as an action movie script. It has survived revolution, war, clumsy restorations and even ‘kidnapping’ and has been threatened with destruction at every turn of these events. So how has it survived for nearly 1,000 years?

Some Reasons for Its Survival

Location, Location, Location

The Bayeux Tapestry has survived due to an extremely fortunate set of circumstances.

Although we do not know how or when the hanging arrived at Bayeux Cathedral, the fact that it did is an important part of its survival story. Stored in a religious setting and given special status, the tapestry was likely displayed only occasionally. As such it was handled less frequently than other hangings that would have adorned secular buildings, meaning there was less opportunity for damage, loss or destruction.

the brief airing evaporated any residual damp … gentle shaking helped shed those threatening larvae

The annual display of the Tapestry carried on unquestioned for decades. The clergy and the citizens of Bayeux barely appreciated its subject matter, but the brief airing evaporated any residual damp, and a gentle shaking helped shed those threatening larvae that had resisted the winter cold or pungent cedar fumes. It was not until the early 18th century that this peaceful routine came under the scrutiny.

Surviving the Roller Coaster of History

The Bayeux Tapestry has also, through history, become an icon for different political personalities such as Napoleon and the Nazis who studied and kept it safe in order to highlight their political messages (that of French military might over the English; and German pan-nationalism respectively). However that has been a double edged sword. Coveting the tapestry also attracts dangerous attention. Other historical events were not so benevolent so the fact that it still exist today, as we shall see, is nothing short of a minor miracle.

Finally, the gradual realisation of the Bayeux Tapestry’s importance as a cultural artefact has ensured that it has been kept safe and well-looked after – particularly in the modern era, by a trained and knowledgeable multi-disciplinary team at the Bayeux Museums Department.

As you will see the tapestry has had an eventful life and the fact it still exists is nothing short of a miracle.

Making the Tapestry

1067 - 1077

1067 - 1077 William’s half-brother,Bishop Odo of Bayeux, was made Earl of Kent and became William’s Deputy in England in the autumn of 1067. It is probably about this time that Bishop Odo ordered the creation of the Bayeux tapestry. Some historians argue that it was embroidered in Kent, probably in Winchester where there was an established embroidery works.

William’s half-brother,Bishop Odo of Bayeux, was made Earl of Kent and became William’s Deputy in England in the autumn of 1067. It is probably about this time that Bishop Odo ordered the creation of the Bayeux tapestry. Some historians argue that it was embroidered in Kent, probably in Winchester where there was an established embroidery works.

First Ever Mention

1476

1476The first ever mention of the Tapestry was in the Inventory of the treasury of the Cathedral Church of Notre-Dame of Bayeux :

“very long and narrow hanging of linen, embroidered with figures and inscriptions representing the Conquest of England, which is hung around the nave of the church on the Feast of Relics [1 July] and throughout the Octave [the eight days following a religious festival] “

Surviving Calvin

1562

1562In 1562 the cathedral was ransacked by French Calvinists. They murdered priests, smashed windows, and stole or destroyed centuries-old treasures including precious textiles and items of gold and silver. Somehow, they overlooked the tapestry. Was it ignored because there were no gold or silver threads in it? Or had it been moved to some safe, hidden place? Another mystery. Another close escape.

Re-Discovery

1690s

1690s The annual display of the Tapestry would have carried on unquestioned for decades. The clergy and the citizens of Bayeux barely appreciating its subject matter. It was not until the early 18th century that this peaceful routine came under the scrutiny of sharp new eyes.

The annual display of the Tapestry would have carried on unquestioned for decades. The clergy and the citizens of Bayeux barely appreciating its subject matter. It was not until the early 18th century that this peaceful routine came under the scrutiny of sharp new eyes.From the end of the 17th and into the early 18th century there was a new interest in the Middle Ages. Learned men toured the provinces, made sketches, wrote up their notes and communicated their findings to colleagues in the local or national societies springing up to feed these passions.

One of these men, Nicolas Joseph Foucault, regional governor of Normandy and committed antiquary came across the tapestry. His immediate reaction was to commission a drawing to record this vital but fragile work.

Foucault’s died in 1721 at the age of 78 at the age of 78.

'Re-Re-Discovery'

1724

1724It wasn’t until after Foucault’s death that his ‘re-discovery’ of the Tapestry had to be again re-discovered by the then Secretary of the prestigious Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, Claude Gros de Boze. De Boze came across Foucault’s drawing whilst going through the books and manuscripts he’d bequeathed to the Académie. De Doze then subsequenty showed it to a fellow-Academicien who specialised in French medieval history, Antoine Lancelot.

On 21 July 1724, Lancelot delivered a paper called ‘L’explication d’un monument de Guillaume le Conquerant’

The tapestry had finally reached the ‘academic light of day’

Revolutionary Peril

1789

1789 In 1789 bloody revolution broke out in France and was to be the greatest threat to the Tapestry’s survival so far.

In 1789 bloody revolution broke out in France and was to be the greatest threat to the Tapestry’s survival so far.For many revolutionaries, destroying the art of the past was one of many ways to wipe out old history in order to make a better future. The new Republican state seized the contents of churches, abbeys and monasteries, and the abandoned buildings were looted and allowed to fall into disrepair. Monks had the choice of reverting to secular status, in return for a meagre pension, or of internment.

Safe in its chest in the corner of a dark side-chapel and not glittering ostentatiously beside an altar, its monarchical (though not blatantly religious) subject matter was not immediately provocative. Other monuments were not so lucky. Most of the statues and paintings in the cathedral and parish churches of Bayeux were destroyed.

Wrappings for Muskets & Boxes

1792

1792Being unobtrusive though was to prove every bit as dangerous as being notable. According to an eye-witness account published in 1838 one man saved it from the mob.

Needing canvas covers, someone remembered the long old hanging stored in the cathedral

In 1792, the National Assembly issued a general call to arms in response to an anticipated English invasion. In Bayeux, volunteers rushed to join the 6th Calvados Battalion, requisitioning carts and wagons to carry their equipment.

Needing canvas covers, someone remembered the long old hanging stored in the cathedral. The municipal council granted permission for its use, and the Tapestry was seized and placed on a wagon. But M. Lambert Leonard-Leforestier, local administrator and commissioner of police, sprang to the rescue by running to his office and dashing off an order to retrieve it. Armed with this, he managed to exchange the precious relic for sheets of sacking. After that, he kept the Tapestry in his own office as a precaution.

Surviving the French Revolution proved once more that Fate was looking after the Tapestry.

Bunting for a Carnival Float

February 1794

February 1794In February 1794 , citizens in ‘a zeal more enthusiastic than enlightened’ wanted to seize the tapestry and chop it up for use in decorating a float carrying the Genius of the Arts in a procession round the town.

This time it was rescued by the newly appointed art commissioners for the Bayeux district, members of a national network set up to preserve the monuments of France.

Official Protection ... at last!

August 1794

August 1794In Paris, the National Convention established a new Commission for Arts (replacing the former Monuments Commission) under the enlightened presidency of Deputy Jean-Baptiste Mathieu.

In an impassioned speech to the Convention on 18 September 1793, Mathieu called for the preservation of works of the past. and the establishment of a register of works of national importance – an enlightened approach to the care of art in dangerous times. He encouraged local groups to rescue, inventory and provide safe-storage depots for vulnerable possessions formerly cared for in churches and chateaux.

In Bayeux, the four commissioners for the district wrote to the mayor to take possession of the Tapestry. After some prevarication the Tapestry was retrieved from the sacristy of the former cathedral, now redesignated a Temple of Reason, and handed over the commissioners. Furthermore they claimed full credit for saving it from imminent destruction at the civic festival (see above).

On 26 August 1794 the commissioners examined the Tapestry, gave it a good dusting and duly reported to the district director that, in accordance with the decree of the Commission, they had now listed the Tapestry and the ivory casket on their inventory of portable antiquities.

It was now safe in one of the national depots, waiting to become ‘the chief ornament of the local museum.

A Dictator's Piece of Propaganda

1803

1803 Napoleon Bonaparte, the ‘Corsican tyrant’, as the English liked to call him, appreciated the function of propaganda.

Napoleon Bonaparte, the ‘Corsican tyrant’, as the English liked to call him, appreciated the function of propaganda.In 1803 Bonaparte become the head of state. In May 1803, despite the fact that England and France were technically at peace, England began to wage ‘preventative’ war on France by blockading French ports and reoccupying ceded territories in the West Indies.

Napoleon decided that the only way to avenge this deceitful behaviour and challenge the enemy’s maritime supremacy was through invasion: he would become the new William the Conqueror.

The inevitable delay in preparing 700 transport barges to ferry his army of 170,000 men to England and the huge costs needed some pre-emptive publicity.

In that autumn of 1803, Paris was hosting a brilliant social season, into which Napoleon brought the Tapestry, snatched from its safe depot under the care of the Bayeux authorities to provide a blatantly public demonstration of how France had once conquered England and would do so again under the right leader- all to justify his inauguration of a risky and very expensive enterprise.

The Bayeux Tapestry proved William’s triumph: Napoleon selected it to predict his own.

Franco Prussian War

1870

1870When France was invaded by German troops during the Franco-Prussian War the Tapestry was packed into a protective zinc cylinder and safely hidden away.

War & Invasion

Sept 1939

Sept 1939War is Declared

On 1 September 1939, Hitler marched into Poland. The Tapestry was taken off exhibition, rolled onto its spool, sprinkled with moth-preventing naphthalene and crushed peppercorns, wrapped up in two sheets and taken down to the cellars, where it was sealed into its crate and locked in the shelter.

Invasion

In May 1940, German forces smashed their way through the Netherlands and Belgium into France, where resistance collapsed. By early June they overran and occupied Normandy and that same month the first German invaders arrived in Bayeux.

Nazi Plots & Plunder

1941-1945

1941-1945Nazi Fascination with the Tapestry

The propaganda value of this famous work of art was well appreciated in Berlin by Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS and of the Gestapo. His interest was deeper and far darker than just its propaganda value. Himmler projected himself as a medieval warlord presiding over the brotherhood of the SS a reincarnation of the glorious medieval Order of Teutonic Knights and the Tapestry was firmly in his sights.

It was also at the mercy of at least 5 different Nazi organisations intent on the rapacious plundering of artefacts from the conquered European territories, especially if they had Jewish owners.

Two of these organisations would be in direct competition to obtain the Tapestry :

- The Kunstschutz : An Arts & Monuments Protection squad, set out to genuinely protect the works of art from damage

- The ‘Ahnenerbe : Formed by Himmler as an SS appendage devoted to the task of promoting the racial doctrines espoused by Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party, specifically by supporting the idea that the modern Germans descended from an ancient Aryan race seen as biologically superior to other racial groups. Later they became out right looters and opportunistic thieves, confiscating Jewish owned artefacts and anything they felt was part of Aryan heritage.

A Plot to Protect It

To protect the tapestry from war damage and the predations of the Ahnenerbe and ERR (another organisation mandated it to seize “Jewish” art collections and other objects of value) the Kunstschutz proposed smuggling the Tapestry to the chateau of Sourches, the most isolated of all the chateaux housing the national collections*. It was near Le Mans in the Sarthe department of western France and 175 kilometres from Bayeux.

*much of the Louvre collections had already been dispersed

The Ahnenerbe Counterstroke

But one of the Kunscschutz’s own staff leaked the plan to smuggle the Tapestry out of Bayeux to the SS-Ahnenerbe. The Ahnenerbe then insisted it be moved to Chateau of Monceau for study and photographing. This project was to be directed by a Professor and was estimated to take six weeks. For the Tapestry’s ‘security’, it would be guarded day and night.

Fortunately, on the 1st August, the Tapestry was returned to Bayeux, where it was put back in the cellar.

Safe at Last?

On the 19 August 1941 the tapestry was finally moved to the majestic 18th century chateau de Sourche. It had been loaned to the Ministry by its owner to store the national collections. Here were kept more than 700 paintings from the Louvre.

On the 19 August 1941 the tapestry was finally moved to the majestic 18th century chateau de Sourche. It had been loaned to the Ministry by its owner to store the national collections. Here were kept more than 700 paintings from the Louvre.The Tapestry was stored in an area in the basement reserved for the most precious possessions, a wooden cellar that already contained five massive crates of very valuable paintings.

Codename ‘Matilda’

ln the spring of 1944, when there were already massive Allied bombing raids over northern France, portents of the great invasion that was suspected, Himmler decided it was time to seize the Tapestry in a secret operation called Sonderauftrag Bretagne (Special Project Brittany): the Tapestry had a codename, ‘Matilda’.

The Ahnenerbe worked out a plan to move the Tapestry to Germany more easily and less suspiciously if it was done in two stages :

- Stage 1 : Arrange for it to come to Paris to be part of one of the many art exhibitions.

- Stage 2 : Once in Paris and in SS hands, it would be easy to spirit the Tapestry out of the country altogether.

It was a good scheme, but the timing was wrong. On 6 June, the Allies landed on the Normandy beaches and Bayeux was liberated, on 8 June.

On 27 June, at about five in the afternoon a group of Gestapo, carrying sub-machine guns, burst into the chateau de Sourche and took the Tapestry to Paris in a period of unimaginable danger for anyone or anything on the move.

“Safe” in Paris

It reached Paris safely and it was placed in the Louvre, devoid of contents except for a very few items of sculpture and carved stone that were simply too large to be moved.

So concerned was Hitler by the speed of the Allied advance that on 3 August he put a new man in charge of Paris. General Oietrich von Choltitz. His orders from Hitler were, in the last resort, to raze the city to the ground rather than leave anything standing in which the Allies could celebrate its recapture.

Yet Himmler could not give the Tapestry up. On 18 August, he sent a radio message to the head of the Gestapo and the SS in France commanding him, as part of the evacuation arrangements, to ‘bring the Tapestry to a place of safety’.

Resistance workers and Parisians had openly risen against the German occupying forces. On Tuesday 22 August , offocers from a e Panzer division arrived to remove the Tapestry. But they were too late under sporadic fire the Louvre was impossible to reach.

Three days later, on 25 August, the Allies liberated Paris.

It wasn’t until 2nd March 1945, however, that the Louvre returned the Tapestry to Bayeux into the care of Mayor Dodeman and Mlle Abraham, its curator.

The Tapestry’s survival intact, against all the odds, proved yet again that it had a charmed life.