Today we celebrate Christmas with a spirit of merriment, gift giving and (over) indulgence. However it may surpise you to know that this outlook on the Christmas season is not actually that old at all. In fact many of our current traditions and attitudes are largely due to the influence of the Victorians in the mid to late 19th Century. So that begs the question … How was Christmas celebrated in the past? Or more specifically for our aricle here – the Middle Ages?

Today we celebrate Christmas with a spirit of merriment, gift giving and (over) indulgence. However it may surpise you to know that this outlook on the Christmas season is not actually that old at all. In fact many of our current traditions and attitudes are largely due to the influence of the Victorians in the mid to late 19th Century. So that begs the question … How was Christmas celebrated in the past? Or more specifically for our aricle here – the Middle Ages?

So if you want to celebrate Christmas in a Medieval style here’s how to do it…

1. Don’t go over the top

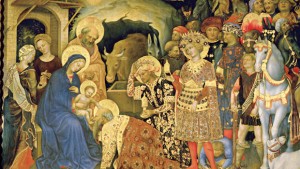

Medieval Christmas wasn’t quite the all-encompassing celebration it often is today. Christmas, the Feast of Jesus’s Nativity, was important, but more significant was Easter, and perhaps also the Annunciation – that moment celebrated on 25 March when God was supposedly conceived in Mary’s womb.

2. Be wary (if you’re not a Christian)

Much of the medieval world didn’t celebrate Christmas at all. Especially if you were a medieval Jew then Christmas could be a time of danger. At Korneuburg in around 1305, townsfolk accused the Jews of procuring a consecrated communion wafer at Christmas and desecrating it, whereupon it ‘bubbled blood-drops, like an egg sweats when it is cooked’. Stories like these – imagining Jews conspiring to attack Jesus’ vulnerable body, present in the wafer – could lead to terrible reprisals.

Much of the medieval world didn’t celebrate Christmas at all. Especially if you were a medieval Jew then Christmas could be a time of danger. At Korneuburg in around 1305, townsfolk accused the Jews of procuring a consecrated communion wafer at Christmas and desecrating it, whereupon it ‘bubbled blood-drops, like an egg sweats when it is cooked’. Stories like these – imagining Jews conspiring to attack Jesus’ vulnerable body, present in the wafer – could lead to terrible reprisals.

The medieval Muslim scholar Ibn Taymiyya (1263–1328) railed against those Muslims who adopted Christian festivities, particularly criticizing what he saw as an imitation of Christmas in the celebration of the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday (mawlid).

3. Fast then feast

For those who did celebrate Christmas then it wasn’t just one day – it was a ‘season of Advent’.

Christmas day was preceded by a month of fasting followed by feasting during the 12 days from 25 December to Epiphany on 6 January.

Advent was seen as a time of special preparation for God’s coming, his adventus, into the world – both in the infant Jesus, and at the end of time at the apocalypse. Advent was supposed to be a time of exile, desire, longing, and repentance.

Fasting was so central to the sacred rhythm of time in medieval Europe that it is no surprise that when reformers wanted to protest against the church in the 16th century, they held a sausage eat-in during a fast!

4. Turn the world upside down – Invert the Social Order

Mirroring pagan traditions (see our article on Saturnalia), inversions of social hierarchy occurred across medieval society around Christmas. One of the most colourful was the election of a boy bishop, who presided over processions and church rituals on the Feast of the Holy Innocents (28 December).

In a surviving example from Old Saint Paul’s in London, the boy bishop wishes that all his schoolteachers would end up on the gallows at Tyburn. One chronicle records how, at the Abbey of St Gall in the 10th century, King Conrad tried to distract the procession of the boys by strewing apples down the processional route; the boys were, however, so disciplined that not an apple was touched.

Inversion could, however, be less controlled: in 1523 at London’s Inns of Court, a ‘lord of misrule’ was responsible for a death.

5. Tree’s and Gifts?

Evergreen trees feature in the ritual life of many cultures, but medieval Christmas trees are hard to trace. We have stray references, particularly from the later middle ages, but their popularity exploded only in the 19th century.

Alternatively, decorate your house with candles and holly and ivy. Gifts were more commonly given not on 25 December, but on New Year’s Day or elsewhere in the Christmas season.

6. Sing Carols or ‘make mickle melodie’

Carols multiplied in the late middle ages – a sign of Christmas’s rising importance. They are often ‘macaronic’ – uniting learned Latin with vernacular languages, and so mixing the high and low, divine and human, in textual form. As devotion to Mary increased, these Christmas songs often hymned her purity

Many of the medieval carols we sing today have had their rhythms regularised and their harmonies rewritten to suit later tastes. If you are a purist, return to the complex rhythms and intricate interweaving lines of manuscript carols. Or you might like to accompany carols with bagpipes, associated with shepherds watching their flocks.

7. Christmas Fayre

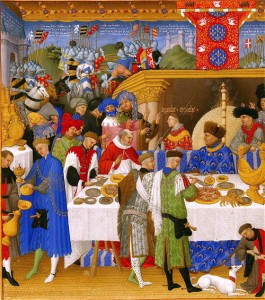

We know the boar’s head was on the medieval menu from the records of the Christmas feasting of Richard de Swinfield, Bishop of Hereford in the 13th century. Along with boar, Richard served beef, venison, partridges, geese, bread, cheese, ale and wine.

Christmas was also a time for charity and sharing food – at Christmas in 1314, some tenants at North Curry in Somerset received loaves of bread, beef and bacon with mustard, chicken soup, cheese and as much beer as they could drink for the day. Gifts of food were sometimes enforced: for the right to keep rabbits, the town of Lagrasse had to give their best bunny to the local monastery each Christmas.

One chief characteristic of medieval food was its seasonal variation, you could only eat what you’d reserved or was available around you at that time of year. Mediaval food was also flavoured with spices like pepper, ginger, cloves and saffron.

Foods you most definately wouldn’t see on the Medieval menu would be chocolate and turkey. They were first brought to Spain under Ferdinand II in the 16th century.