Vraicing on Guernsey

Few island customs, except perhaps the Clameur de Haro, which survive today can claim as ancient a history as that of ” vraicing.” In 1607 Royal Commissioners sent to the island by James I were petitioned by the inhabitants to perpetuate their

“ancient right to gather vraic without they be in any way hindered, forasmuch as they can have no com without they have that liberty.”

Even then the island saying “point de vraic, point de hautgard —no seaweed, no cornyard”—had become a local proverb.

Types of Seaweed

There were two classes of seaweed which are gathered, “vraic scie” and “vraic venant.” The former is attached to the rocks and is cut off by bill-hooks or sickles and is worth two or three times as much as the vraic venant which is drift-weed. Both were used as fertiliser and their value as such varied with the time of year, the summer crop being superior to that gathered in winter.

Applying it to the Land

In olden times it was also used as fuel and as stuffing for the “lit de fouaille ” or greenbed. However as fertiliser it was be applied to the ground while fresh and allowed to rot, or it may be dried first and ploughed or dug in. Alternatively, a popular and convenient form of use is as ashes after burning, such residue being rich in potash, iron, iodine and other mineral salts.

Harvesting

The seasons for harvesting of vraic have always been controlled by the Guernsey Court of Chief Pleas, and these have varied during the centuries.

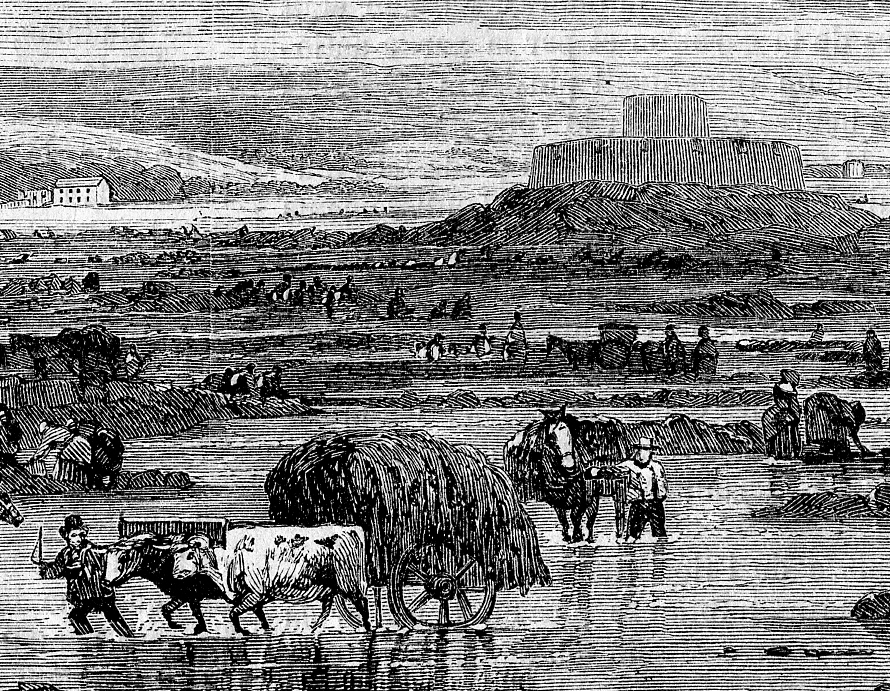

During the early 19th Century the loads taken from Guernsey and Herm annually were estimated at about 30,000 of a value then of some £3,000. Today, modern farmimg methods have largely replaced the gathering of vraic which has led to problems of a build up of noxious piles of seaweed, as can be seen in this Guernsey Press artice of 2009

Celebrating the Vraic Harvest

Islanders no longer celebrate the harvesting of this crop as their ancestors did. In time pass bands of youths and yoiug girls, with garlands of flowers in their hair, wielded the great rakes which had heads between two and three feet long, teeth of fourteen inches, and a sapling handle from twelve to eighteen feet in length. When the tide turned and the heaps were safely stacked beyond its reach, the harvesters relaxed in a communal bathing parade while their elders prepared the gargantuan feast that included all varieties of “gache” to which the appetites of all present no doubt did full justice.

Afterwards the rest of the night was spent in dancing and, to judge by contemporary records, a good time was had by all.

Today those who go down to the sea by slips to gather vraic no longer wear garlands in their hair, but the loads they bring back with them are still highly prized—and priced.