The years following the French Revolution in 1789 were dramatic in the history of the island. Many emigres found refuge in Guernsey and the island even ended up as a centre for a spy network operating against the newly formed republic.

Boomtime Guernsey

Boomtime Guernsey

In the late 18th century Guernsey was flourishing, experiencing something of an economic boom.

St Peter Port was a ‘free port’ – an entrepot for international business. Large quantities of gin from Rotterdam, brandy from Spain and France, rum from the West Indies, tobacco from Virginia. Some 4-5 million gallons of spirits were being imported annually into the island – almost all for sale to English wholesalers and smugglers.

The cultural life of St Peter Port was on something of a high also with a population rising rapidly above 7,500. The town could boast over a hundred taverns and wine shops. There were printing-presses, coffee-houses, clubs, assembly rooms, masonic lodges, academies, lending libraries, and shops stocked with fashionable textiles from Paris, Lyons and England. Touring companies of actors presented plays in French and English. Elegant, ornamental gardens were tended by migrant workers.

the early days of the French Revolution did not shock the island

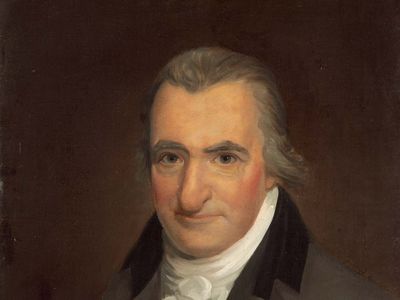

Many of the aristocratic young men of the island rejected the conservative values of the ‘government by the few’ and espoused the libertarian ideals as expressed by the founders of the new American republic and by English agitators such as Thomas Paine (see panel below). It is therefore not surprising that the early days of the French Revolution did not particularly shock the island.

Thomas Paine : British-American Author

| Born | : | January 29, 1737 Thetford, England |

| Died | : | June 8, 1809 (aged 72) New York City, New York |

English-American writer and political pamphleteer. Regarded as one of the greatest political propagandists in history. His “Common Sense” pamphlet and Crisis papers were important influences on the American Revolution.

Important Works

- Common Sense (1775–1776) – Pamphlet advocating independence from Great Britain to people in the 13 American Colonies

- Rights of Man (1791) – A defense of the French Revolution and of republican principles

- The Age of Reason (3 parts : 1794, 1795 & 1807) – An exposition of the place of religion in society

The Turning Point

The Turning Point

That was to change when the tempo of the Revolution accelerated.

Ideas about moderate constitutional reform gave way to an open assault on the French aristocracy and its privileges. The church was increasingly attacked.

In September 1792, the French Legislative Assembly legalized divorce, contrary to Catholic doctrine. At the same time, the French State took control of the birth, death, and marriage registers away from the Church. An ever-increasing view that the Church was a counter-revolutionary force exacerbated the social and economic grievances and violence erupted in towns and cities across France.

The Émigrés

The Émigrés

A trickle of refugees soon became a flood. It has been estimated that altogether about 150,000 French aristocrats, bourgeoisie and priests left France to find refuge in foreign lands as émigrés. According to one calculation at one time during this period an estimated 11,000 of these refugees were in the Channel Islands alone.

The sudden influx of émigrés caused a shortage of food; emergency measures had to be taken to ship extra supplies of corn from England to the Channel Islands.

The émigrés met a mixed reception in Guernsey. The journalist-printer Chevalier published a stinging polemic against the aristos in the Gazette de Guernesey.

Many of the émigrés lived in reduced circumstances and had to work to support themselves and their families. They gave lessons in dancing, fencing and drawing; copied music; carved ivory; or worked hair as ornaments.

Bloody Revolution & ‘Madame La Guillotine’

Bloody Revolution & ‘Madame La Guillotine’

During 1792 France slid into war with Austria and Prussia. However trade with Guernsey continued as usual for the time being.

During 1792 France slid into war with Austria and Prussia. However trade with Guernsey continued as usual for the time being.

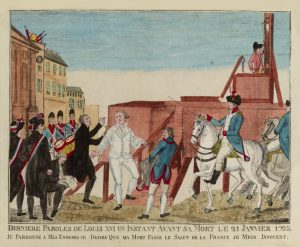

This was to change in September 1792 when the Assemblé Nationale decreed that animals and comestibles should no longer be exported from France to the Channel Islands. And when, in January 1793 the French monarch was put on trial and then executed, it became quite clear that the revolutionaries were bent on measures far more extreme than securing a constitutional monarchy. The shine and excitement felt in Guernsey about a new world order coming to pass in the heady early days of ‘La Revolution’ had worn off.

War

War

In February 1793 France declared war against Britain. The Channel Islands immediately resumed their centuries-old strategic importance. Local shipowners and merchants applied for letters-of-marque so that they could embark on privateering voyages.

Privateers are effectively state licensed private warships. Private individual can equip their own vessels for war and are licensed to seize and plunder enemy shipping. The master had to hold a licence from the Government called a Letter of Marque. Between 1793 and 1801 235 such letters were issued by the English authorities to captains of Guernsey ships.

The garrison of British soldiers on Guernsey was reinforced and the Guernsey Milita’s training took on a more urgent tone. The Militia could muster over 3,000 boys and men and served as a valuable additional force to the regular British soldiers on the island.

Espionage

Espionage

The Channel Islands served as a vital staging-post for the British secret service. Even before the Revolutionary war Guernsey had been a centre for naval intelligence.

In March 1793 peasants in the Vendee in France rose in revolt against the new Republic. The British government and French royalist émigrés saw the possibilities of exploiting this situation. An existing network of spies was expanded to bring news from Brittany to the Channel Islands (Jersey in particular) and thence to England. Agents could be sent through this network into France to help to organise the counter-revolution. This spy network was known as la Correspondance and the agents usually operated under code-names. The head of the correspondance in Guernsey was Monsieur de Vossey, alias Le Juste (the right word).

British hopes were further raised by the counter-revolution of the Chouans in Brittany. Agents, money and supplies were sent via the Correspondance to Breton sympathisers.

French Royalist Forces

French Royalist Forces

Guernsey was used by both the French Royalists and the British government as a base for building up an army of émigrés who could invade mainland France. Several companies were raised between 1793 and 1796 but their objectives were not achieved.

French Plans to Invade the Islands

French Plans to Invade the Islands

The Channel Islands were on the front line of the ever developing war. In January 1794 the Committee of Public Safety in Paris drew up orders for the launching of an invasion of the Channel Islands.

The scale of the proposed attack was huge. An army of 20,000 infantry, 200 to 300 cavalry and 200 artillery pieces were to be used (10,000 on Guernsey alone). Jersey, Guernsey and Alderney were to be attacked simultaneously.

The Channel Islands Attack :

The Guernsey Attack :

- 4 ships of the line to bombard Castle Cornet

- Transport vessels carrying mortars were to shell St Peter Port.

- St Martin’s battery to be attacked by the guns of 2 ships of the line

- Gunboats to attack St Peter Port harbour covering the landing of 10,000 men

- Any vessels attempting to leave Guernsey to be intercepted by corvettes and despatch boats

- Any and all resistance to be crushed

- All French émigrés in the islands were to be immediately condemned to death and executed

The French had good reason for wishing to invade the islands. At a stroke they could have eliminated the spies and émigrés who were so busy plotting mischief both with Royalist sympathisers in Brittany and with the peasant counter-revolutionaries known as the Chouans. The Correspondance would have been destroyed. The islanders would no longer have been able to engage in privateering against French coastal shipping. The islands would no longer have served as a forward-post for the British army and navy. Rather, the French could have employed Guernsey as a well defended port from which to harass the British fleet and to threaten landings in England.

Fortunately the invasion was never launched.

If you want to read more on this subject we can heartily recommend Dr Gregory Stevens Cox’s book of the same name “Guernsey & the French Revolution” from which this article was mostly written.

If you want to read more on this subject we can heartily recommend Dr Gregory Stevens Cox’s book of the same name “Guernsey & the French Revolution” from which this article was mostly written.