At the start of this article we should really point out that at present there’s no real hard proof that animals can detect earthquakes or other seismic events. HOWEVER there is enough other evidence to warrant a serious discussion and debate on the issue. We look here at some intriguing observations and some basix research that has been done.

At the start of this article we should really point out that at present there’s no real hard proof that animals can detect earthquakes or other seismic events. HOWEVER there is enough other evidence to warrant a serious discussion and debate on the issue. We look here at some intriguing observations and some basix research that has been done.

Intriguing Observations

A few days after the Indian Ocean tsunami struck on 26 December 2004, reports began to emerge of strangely low levels of fatalities among wildlife. According to officials at the Yala National Park in Sri Lanka, where 60 people lost their lives, not a single dead animal was found – despite it being one of the worst-hit areas. Most striking of all were the reports from India’s Cuddalore coast, where thousands of people died, while buffalo, goats and other animals seemed to have escaped unscathed.

One might be scepptical of these ‘observations’ after the event, however reports have been confirmed by many witnesses, who reported seeing elephants running for higher ground, flamingos leaving their low-lying breeding grounds and other strange behaviours.

While these tie in with accounts following many other major seismic events, sceptics rightly object that they may all be post hoc rationalizations. After all, spend enough time at your local duck pond, and you’ll witness “strange behaviour” just before, for example, a bomb attack in Baghdad. Some scientists have also pointed out that the intervals between major earthquakes are too long to allow animals to associate what they are sensing with memories of past disasters or give much scope for evolution to promote the emergence of quake-sensing traits.

Explanations ?

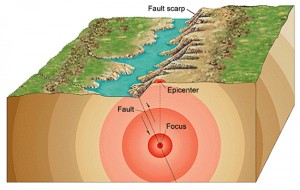

Such arguments are far from compelling: perhaps the animals are benefiting from sensory abilities acquired for other reasons, such as communication. In 1997, researchers at the University of California reported that elephants could detect the stomping of others over distances of more than 30 miles. Or maybe the animals were responding to the faint seismic effects that often presage major quakes; there were plenty of those in the run up to the Sumatra quake – the area had been struck by three of the seven most powerful quakes recorded anywhere in the world in 2004.

Such arguments are far from compelling: perhaps the animals are benefiting from sensory abilities acquired for other reasons, such as communication. In 1997, researchers at the University of California reported that elephants could detect the stomping of others over distances of more than 30 miles. Or maybe the animals were responding to the faint seismic effects that often presage major quakes; there were plenty of those in the run up to the Sumatra quake – the area had been struck by three of the seven most powerful quakes recorded anywhere in the world in 2004.

Alternatively, they might have sensed electromagnetic disturbances that some scientists claim accompany the fracturing of rock before a quake. In 1998, a team of scientists in Japan examined this possibility by watching the behaviour of laboratory animals as blocks of granite were mechanically crushed nearby. As the pressure on the blocks mounted, the animals became increasingly nervous and this appeared to be linked to the emergence of electromagnetic effects from the crushed rocks. The team suggested that this may explain how some animals seem able to sense major quakes hours or even days ahead.

The terrible events of December 2004 should surely prompt more research into this fascinating possibility.