OPERATION ASTERIX

Discovery

On Christmas Day 1982 local Diver Richard Keen spotted the remains of a large wreck sticking out from the mud directly between the pierheads of St Peter Port harbour. The wreck had been exposed by the prop-wash of various new ferries being used on the Guernsey shipping routes and it soon became apparent that it and was being quickly destroyed. It was identified as Roman and ‘The Guernsey Maritime Trust’ was formed and tasked with rescuing the ship.

By coincidence, a Roman waterfront site at La Plaiderie was excavated by Bob Burns of Guernsey Museum during the same period. Until this double find, there was very little to indicate that the Romans even came to Guernsey.

Thus it was that between 1984 and 1986, archaeologists led by Dr Margaret Rule teamed up with local divers from the Blue Dolphin club to excavate the ship and it was during this time that a schoolboy watching the diving asked whether this was ‘Asterix’s ship’ and so the name stuck and the ship became known locally as ‘Asterix’.

Excavation

The stem of the ship was still in place, held down by a great mass of pine tar. Asterix had caught fire whilst in the Roman harbour and it had been carrying pine tar in blocks in its aft hold. These melted in the fire, trapping over a thousand objects from the burning ship. When the ship sank, the fire was put out and the tar set in a solid mass.

This stroke of luck meant that timbers at the stern were preserved in such detail that the marks of saws, axes and other tools could still be seen on them. Trapped objects included roof tile and pottery from Algeria, Spain, France and Britain. Even leftover food was stuck in the bilge at the bottom of the ship. Eighty coins were found, the latest dating to after AD 275, suggesting the ship sank about AD280.

As the nails holding the ship together had dissolved over the centuries, the ship was able to be lifted piece by piece between 1984-87 with the timbers being recorded in detail then soaked in fresh water to remove the salt and dead sea creatures.

In 1999 they were sent to the Mary Rose Trust in Portsmouth for conservation. The timbers were soaked in water-soluble wax (PEG) which replaced the water in the wood, stopping them from cracking when they dry out. To finish off they were loaded into a giant freeze-drier to drive off the water. The whole process took 13 years and Asterix wasn’t returned ‘home’ until January 2015.

ASTERIX IN CONTEXT

The Third Century Roman Empire

Asterix has been dated to approximately 280.A.D. – a time of considerable instability in the Roman Empire especially around Britian and Gaul. Between 200-300 A.D there were a series of wars, rebellions and barbarian invasions with on average each Emperor ruling for just 4 years before being dieing in various ways – mostly by assassination.

Between 260 and 274 A.D. both Gaul and Britain had broken away from Rome to form the ‘Gallic Empire’.

So it’s against this backdrop that Asterix – actually a Celtic-Romao style ship – sailed into St Peter Port one day, caught fire and sank. We will never know how or why she caught fire but it’s tempting to think that maybe the period of upheaval in this corner of the Empire had something to do with it – we shall probably never know.

Asterix In Detail

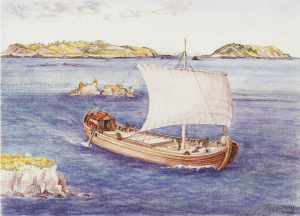

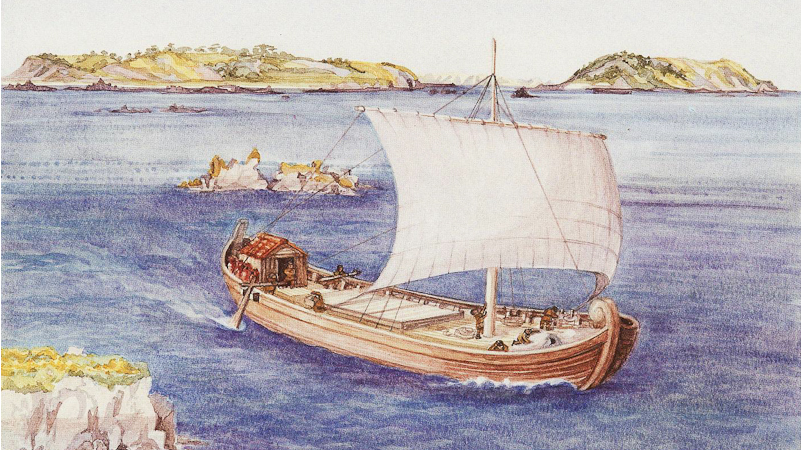

Just over 17 meters of the bottom of the ship survived but she would originally have been at least 22 meters long at the waterline and possibly 25 meters overall. The maximum beam (width) of the ship would have been around 6 meters. No carpentered joints were used in building the hull, which was held together with huge nails. She was a Celtic design of ship which is thought to have been used extensively in these waters for over 450 years before sinking. Parts of two smaller boats using a similar design have been found in Britain. True Roman ships were built completely differently.

Just over 17 meters of the bottom of the ship survived but she would originally have been at least 22 meters long at the waterline and possibly 25 meters overall. The maximum beam (width) of the ship would have been around 6 meters. No carpentered joints were used in building the hull, which was held together with huge nails. She was a Celtic design of ship which is thought to have been used extensively in these waters for over 450 years before sinking. Parts of two smaller boats using a similar design have been found in Britain. True Roman ships were built completely differently.

Each floor timber was made from the trunk of an oak tree at the point where it meets a large bough. They weighed up to 250kg each and were fastened to the outer planking of the hull by iron nails up to 70cm long. Some of floor timbers are marked with two slots on its inner surface and a ridge running across its aft edge so we know that here there would have been a bulkhead (internal wall) would have separated the main hold of the ship from the aft hold.

Ingenious semicircular ‘timber holes’ were cut on the undersides to allow water to run from the back of the ship into the bilge, where it could be pumped out. Part of the bilge pumping mechanism was also recovered from the wreck.

Although the bow was missing from the wreck it is believed that it was probably similar shape to the stern making the ship double-ended. It would have been steered by a ‘steering oar’ rather than a rudder.

Finds from the wreck show that the ship had a galley at the back, with an oven and a tile roof. The ship had a flat bottom which was double the thickness of the rest of the planking. Asterix could beach like a landing craft in order to unload cargo or avoid bad weather. It was a good design because in Roman times Guernsey, Britain and Gaul had few proper harbours.

Bilge Pump

A bronze bilge bearing, along with a second one, was found embedded in the tar on the wreck and would have been fixed to a wooden frame. A hole in the centre carried a rotating shaft, possibly with a handle so that it could be turned. The two bearings formed part of a pump used to remove water from the bottom of the ship (the bilge). Similar objects have been found on Roman wrecks in the Mediterranean.

A bronze bilge bearing, along with a second one, was found embedded in the tar on the wreck and would have been fixed to a wooden frame. A hole in the centre carried a rotating shaft, possibly with a handle so that it could be turned. The two bearings formed part of a pump used to remove water from the bottom of the ship (the bilge). Similar objects have been found on Roman wrecks in the Mediterranean.

ROMAN DECLINE & FALL IN THE CHANNEL ISLANDS

Troubled Times

As we have already mentioned ‘Asterix’ sank at a time of growing trouble for the Romans. The Western Roman Empire suffered increasing crises during the third and fourth centuries. ‘Barbarians’ such as the Saxons raided the eastern borders and coasts and there were frequent rebellions by generals. Forts were built to guard the coasts of Britain and Gaul (France).

A Roman small fort was built in Alderney, probably as a base for naval patrols against pirates and raiders. At some time between AD400 and AD500, Guernsey ceased to be controlled by Rome. Archaeologists are only just beginning to understand Roman Guernsey and many questions remain.

The Nunnery Roman Fort

The Roman fort at the Nunnery, Alderney, is approximately 40 metres square. It has rounded corners with semicircular bastions that may have been designed to carry bolt-shooting engines (ballistae). Orginally it had a massive square tower in the centre, with walls 2.8 metres thick. This is the best surviving Roman small fort in Britain. Archaeologists believe it was constructed in the middle of the fourth century to protect Roman naval patrol ships based in Longis Bay. The reconstruction is by artist Doug Hamon.

The Roman fort at the Nunnery, Alderney, is approximately 40 metres square. It has rounded corners with semicircular bastions that may have been designed to carry bolt-shooting engines (ballistae). Orginally it had a massive square tower in the centre, with walls 2.8 metres thick. This is the best surviving Roman small fort in Britain. Archaeologists believe it was constructed in the middle of the fourth century to protect Roman naval patrol ships based in Longis Bay. The reconstruction is by artist Doug Hamon.

You must be logged in to post a comment.